Даниэль Дефо

History of the Plague in London

INTRODUCTION

The father of Daniel Defoe was a butcher in the parish of St. Giles's, Cripplegate, London. In this parish, probably, Daniel Defoe was born in 1661, the year after the restoration of Charles II. The boy's parents wished him to become a dissenting minister, and so intrusted his education to a Mr. Morton who kept an academy for the training of nonconformist divines. How long Defoe staid at this school is not known. He seems to think himself that he staid there long enough to become a good scholar; for he declares that the pupils were "made masters of the English tongue, and more of them excelled in that particular than of any school at that time." If this statement be true, we can only say that the other schools must have been very bad indeed. Defoe never acquired a really good style, and can in no true sense be called a "master of the English tongue."

Nature had gifted Defoe with untiring energy, a keen taste for public affairs, and a special aptitude for chicanery and intrigue. These were not qualities likely to advance him in the ministry, and he wisely refused to adopt that profession. With a young man's love for adventure and a dissenter's hatred for Roman Catholicism, he took part in the Duke of Monmouth's rebellion (1685) against James II. More fortunate than three of his fellow students, who were executed for their share in this affair, Defoe escaped the hue and cry that followed the battle of Sedgemoor, and after some months' concealment set up as a wholesale merchant in Cornhill. When James II. was deposed in 1688, and the Protestant William of Orange elected to the English throne, Defoe hastened to give in his allegiance to the new dynasty. In 1691 he published his first pamphlet, "A New Discovery of an Old Intrigue, a Satire leveled at Treachery and Ambition." This is written in miserable doggerel verse. That Defoe should have mistaken it for poetry, and should have prided himself upon it accordingly, is only a proof of how incompetent an author is to pass judgment upon what is good and what is bad in his own work.

In 1692 Defoe failed in business, probably from too much attention to politics, which were now beginning to engross more and more of his time and thoughts. His political attitude is clearly defined in the title of his next pamphlet, "The Englishman's Choice and True Interest: in the Vigorous Prosecution of the War against France, and serving K. William and Q. Mary, and acknowledging their Right." "K. William" was too astute a manager to neglect a writer who showed the capacity to become a dangerous opponent. Defoe was accordingly given the place of accountant to the commissioners of the glass duty (1694). From this time until William's death (1702), he had no more loyal and active servant than Defoe. Innumerable pamphlets bear tribute to his devotion to the King and his policy, – pamphlets written in an easy, swinging, good-natured style, with little imagination and less passion; pamphlets whose principal arguments are based upon a reasonable self-interest, and for the comprehension of which no more intellectual power is called for than Providence has doled out to the average citizen. Had Defoe lived in the nineteenth century, instead of in the seventeenth, he would have commanded a princely salary as writer for the Sunday newspaper, and as composer of campaign documents and of speeches for members of the House of Representatives.

In 1701 Defoe published his "True-born Englishman," a satire upon the English people for their stupid opposition to the continental policy of the King. This is the only metrical composition of prolific Daniel that has any pretensions to be called a poem. It contains some lines not unworthy to rank with those of Dryden at his second-best. For instance, the opening: —

"Wherever God erects a house of prayer,

The Devil always builds a chapel there;

And 'twill be found upon examination

The latter has the largest congregation."

Or, again, this keen and spirited description of the origin of the English race: —

"These are the heroes that despise the Dutch,

And rail at newcome foreigners so much,

Forgetting that themselves are all derived

From the most scoundrel race that ever lived;

A horrid crowd of rambling thieves and drones,

Who ransacked kingdoms and dispeopled towns:

The Pict and painted Briton, treach'rous Scot

By hunger, theft, and rapine hither brought;

Norwegian pirates, buccaneering Danes,

Whose red-haired offspring everywhere remains:

Who, joined with Norman French, compound the breed

From whence your true-born Englishmen proceed."

Strange to say, the English people were so pleased with this humorous sketch of themselves, that they bought eighty thousand copies of the work. Not often is a truth teller so rewarded.

Not unnaturally elated by the success of this experiment, the next year Defoe came out with his famous "Shortest Way with the Dissenters," a satire upon those furious High Churchmen and Tories, who would devour the dissenters tooth and nail. Unfortunately, the author had overestimated the capacity of the average Tory to see through a stone wall. The irony was mistaken for sincerity, and quoted approvingly by those whom it was intended to satirize. When the truth dawned through the obscuration of the Tories' intellect, they were naturally enraged. They had influence enough to have Defoe arrested, and confined in Newgate for some eighteen months. He was also compelled to stand in the pillory for three days; but it is not true that his ears were cropped, as Pope intimates in his

"Earless on high stood unabashed Defoe."

What are the exact terms Defoe made with the ministry, and on exactly what conditions he was released from Newgate, have not been ascertained. It is certain he never ceased to write, even while in prison, both anonymously and under his own name. For some years, in addition to pamphlet after pamphlet, he published a newspaper which he called the "Review,"1 in which he generally sided with the moderate Whigs, advocated earnestly the union with Scotland, and gave the English people a vast deal of good advice upon foreign policy and domestic trade. There is no doubt that during this time he was in the secret service of the government. When the Tories displaced the Whigs in 1710, he managed to keep his post, and took his "Review" over to the support of the new masters, justifying his turncoating by a disingenuous plea of preferring country to party. His pamphleteering pen was now as active in the service of the Tory prime minister Harley as it had been in that of the Whig Godolphin. The party of the latter rightly regarded him as a traitor to their cause, and secured an order from the Court of Queen's Bench, directing the attorney-general to prosecute Defoe for certain pamphlets, which they declared were directed against the Hanoverian succession. Before the trial took place, Harley, at whose instigation the pamphlets had been written, secured his henchman a royal pardon.

When the Tories fell from power at the death of Queen Anne (1714), and the Whigs again obtained possession of the government, only one of two courses was open to Defoe: he must either retire permanently from politics, or again change sides. He unhesitatingly chose the latter. But his political reputation had now sunk so low, that no party could afford the disgrace of his open support. He was accordingly employed as a literary and political spy, ostensibly opposing the government, worming himself into the confidence of Tory editors and politicians, using his influence as an editorial writer to suppress items obnoxious to the government, and suggesting the timely prosecution of such critics as he could not control. He was able to play this double part for eight years, until his treachery was discovered by one Mist, whose "Journal" Defoe had, in his own words, "disabled and enervated, so as to do no mischief, or give any offense to the government." Mist hastened to disclose Defoe's real character to his fellow newspaper proprietors; and in 1726 we find the good Daniel sorrowfully complaining, "I had not published my project in this pamphlet, could I have got it inserted in any of the journals without feeing the journalists or publishers… I have not only had the mortification to find what I sent rejected, but to lose my originals, not having taken copies of what I wrote."2 Heavy-footed justice had at last overtaken the arch liar of his age.

Of the two hundred and fifty odd books and pamphlets written by Defoe, it may fairly be said that only two – "Robinson Crusoe" and the "History of the Plague in London" – are read by any but the special students of eighteenth-century literature. The latter will be discussed in another part of this Introduction. Of the former it may be asserted, that it arose naturally out of the circumstances of Defoe's trade as a journalist. So long as the papers would take his articles, nobody of distinction could die without Defoe's rushing out with a biography of him. In these biographies, when facts were scanty, Defoe supplied them from his imagination, attributing to his hero such sentiments as he thought the average Londoner could understand, and describing his appearance with that minute fidelity of which only an eyewitness is supposed to be capable. Long practice in this kind of composition made Defoe an adept in the art of "lying like truth." When, therefore, the actual and extraordinary adventures of Alexander Selkirk came under his notice, nothing was more natural and more profitable for Defoe than to seize upon this material, and work it up, just as he worked up the lives of Jack Sheppard the highwayman, and of Avery the king of the pirates. It is interesting to notice also that the date of publication of "Robinson Crusoe" (1719) corresponds with a time at which Defoe was playing the desperate and dangerous game of a political spy. A single false move might bring him a stab in the dark, or might land him in the hulks for transportation to some tropical island, where he might have abundant need for the exercise of those mental resources that interest us so much in Crusoe. The secret of Defoe's life at this time was known only to himself and to the minister that paid him. He was almost as much alone in London as was Crusoe on his desert island.

The success which Defoe scored in "Robinson Crusoe" he never repeated. His entire lack of artistic conscience is shown by his adding a dull second part to "Robinson Crusoe," and a duller series of serious reflections such as might have passed through Crusoe's mind during his island captivity. Of even the best of Defoe's other novels, – "Moll Flanders," "Roxana," "Captain Singleton," – the writer must confess that his judgment coincides with that of Mr. Leslie Stephen, who finds two thirds of them "deadly dull," and the treatment such as "cannot raise [the story] above a very moderate level."3

The closing scenes of Defoe's life were not cheerful. He appears to have lost most of the fortune he acquired from his numerous writings and scarcely less numerous speculations. For the two years immediately preceding his death, he lived in concealment away from his home, though why he fled, and from what danger, is not definitely known. He died in a lodging in Ropemaker's Alley, Moorfields, on April 26, 1731.

The only description we have of Defoe's personal appearance is an advertisement published in 1703, when he was in hiding to avoid arrest for his "Shortest Way with the Dissenters: " —

"He is a middle-aged, spare man, about forty years old, of a brown complexion, and dark-brown colored hair, but wears a wig; a hooked nose, a sharp chin, gray eyes, and a large mole near his mouth."

In the years 1720-21 the plague, which had not visited Western Europe for fifty-five years, broke out with great violence in Marseilles. About fifty thousand people died of the disease in that city, and great alarm was felt in London lest the infection should reach England. Here was a journalistic chance that so experienced a newspaper man as Defoe could not let slip. Accordingly, on the 17th of March, 1722, appeared his "Journal of the Plague Year: Being Observations or Memorials of the most Remarkable Occurrences, as well Publick as Private, which happened in London during the Last Great Visitation in 1665. Written by a Citizen who continued all the while in London. Never made public before." The story is told with such an air of veracity, the little circumstantial details are introduced with such apparent artlessness, the grotesque incidents are described with such animation, (and relish!) the horror borne in upon the mind of the narrator is so apparently genuine, that we can easily understand how almost everybody not in the secret of the authorship believed he had here an authentic "Journal," written by one who had actually beheld the scenes he describes. Indeed, we know that twenty-three years after the "Journal" was published, this impression still prevailed; for Defoe is gravely quoted as an authority in "A Discourse on the Plague; by Richard Mead, Fellow of the College of Physicians and of the Royal Society, and Physician to his Majesty. 9th Edition. London, 1744." Though Defoe, like his admiring critic Mr. Saintsbury, had but small sense of humor, even he must have felt tickled in his grave at this ponderous scientific tribute to his skill in the art of realistic description.

If we inquire further into the secret of Defoe's success in the "History of the Plague," we shall find that it consists largely in his vision, or power of seeing clearly and accurately what he describes, before he attempts to put this description on paper. As Defoe was but four years old at the time of the Great Plague, his personal recollection of its effects must have been of the dimmest; but during the years of childhood (the most imaginative of life) he must often have conversed with persons who had been through the plague, possibly with those who had recovered from it themselves. He must often have visited localities ravaged by the plague, and spared by the Great Fire of 1666; he must often have gazed in childish horror at those awful mounds beneath which hundreds of human bodies lay huddled together, – rich and poor, high and low, scoundrel and saint, – sharing one common bed at last. His retentive memory must have stored away at least the outline of those hideous images, so effectively recombined many years later by means of his powerful though limited imagination.

Defoe had the ability to become a good scholar, and to acquire the elements of a good English style; but it is certain he never did. He never had time, or rather he never took time, preferring invariably quantity to quality. What work of his has survived till to-day is read, not for its style, but in spite of its style. His syntax is loose and unscholarly; his vocabulary is copious, but often inaccurate; many of his sentences ramble on interminably, lacking unity, precision, and balance. Figures of speech he seldom abuses because he seldom uses; his imagination, as noticed before, being extremely limited in range. That Defoe, in spite of these defects, should succeed in interesting us in his "Plague," is a remarkable tribute to his peculiar ability as described in the preceding paragraph.

In the course of the Notes, the editor has indicated such corrections as are necessary to prevent the student from thinking that in reading Defoe he is drinking from a "well of English undefiled." The art of writing an English prose at once scholarly, clear-cut, and vigorous, was well understood by Defoe's great contemporaries, Dryden, Swift, and Congreve; it does not seem to have occurred to Defoe that he could learn anything from their practice. He has his reward. "Robinson Crusoe" may continue to hold the child and the kitchen wench; but the "Essay on Dramatic Poesy," "The Battle of the Books," and "Love for Love," are for the men and women of culture.

The standard Life of Defoe is by William Lee (London, J.C. Hotten, 1869). William Minto, in the "English Men of Letters Series," has an excellent short biography of Defoe. For criticism, the only good estimate I am acquainted with is by Leslie Stephen, in "Hours in a Library, First Series." The nature of the article on Defoe in the "Britannica" may be indicated by noticing that the writer (Saintsbury) seriously compares Defoe with Carlyle as a descriptive writer. It would be consoling to think that this is intended as a joke.

Those who wish to know more about the plague than Defoe tells them should consult Besant's "London," pp. 376-394 (New York, Harpers). Besant refers to two pamphlets, "The Wonderful Year" and "Vox Civitatis," which he thinks Defoe must have used in writing his book.

HISTORY

OF

THE PLAGUE IN LONDON

It was about the beginning of September, 1664, that I, among the rest of my neighbors, heard in ordinary discourse that the plague was returned again in Holland; for it had been very violent there, and particularly at Amsterdam and Rotterdam, in the year 1663, whither, they say, it was brought (some said from Italy, others from the Levant) among some goods which were brought home by their Turkey fleet; others said it was brought from Candia; others, from Cyprus. It mattered not from whence it came; but all agreed it was come into Holland again.4

We had no such thing as printed newspapers in those days, to spread rumors and reports of things, and to improve them by the invention of men, as I have lived to see practiced since. But such things as those were gathered from the letters of merchants and others who corresponded abroad, and from them was handed about by word of mouth only; so that things did not spread instantly over the whole nation, as they do now. But it seems that the government had a true account of it, and several counsels5 were held about ways to prevent its coming over; but all was kept very private. Hence it was that this rumor died off again; and people began to forget it, as a thing we were very little concerned in and that we hoped was not true, till the latter end of November or the beginning of December, 1664, when two men, said to be Frenchmen, died of the plague in Longacre, or rather at the upper end of Drury Lane.6 The family they were in endeavored to conceal it as much as possible; but, as it had gotten some vent in the discourse of the neighborhood, the secretaries of state7 got knowledge of it. And concerning themselves to inquire about it, in order to be certain of the truth, two physicians and a surgeon were ordered to go to the house, and make inspection. This they did, and finding evident tokens8 of the sickness upon both the bodies that were dead, they gave their opinions publicly that they died of the plague. Whereupon it was given in to the parish clerk,9 and he also returned them10 to the hall; and it was printed in the weekly bill of mortality in the usual manner, thus: —

Plague, 2. Parishes infected, 1.

The people showed a great concern at this, and began to be alarmed all over the town, and the more because in the last week in December, 1664, another man died in the same house and of the same distemper. And then we were easy again for about six weeks, when, none having died with any marks of infection, it was said the distemper was gone; but after that, I think it was about the 12th of February, another died in another house, but in the same parish and in the same manner.

This turned the people's eyes pretty much towards that end of the town; and, the weekly bills showing an increase of burials in St. Giles's Parish more than usual, it began to be suspected that the plague was among the people at that end of the town, and that many had died of it, though they had taken care to keep it as much from the knowledge of the public as possible. This possessed the heads of the people very much; and few cared to go through Drury Lane, or the other streets suspected, unless they had extraordinary business that obliged them to it.

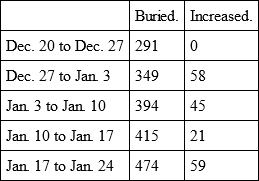

This increase of the bills stood thus: the usual number of burials in a week, in the parishes of St. Giles-in-the-Fields and St. Andrew's, Holborn,11 were12 from twelve to seventeen or nineteen each, few more or less; but, from the time that the plague first began in St. Giles's Parish, it was observed that the ordinary burials increased in number considerably. For example: —

The like increase of the bills was observed in the parishes of St. Bride's, adjoining on one side of Holborn Parish, and in the parish of St. James's, Clerkenwell, adjoining on the other side of Holborn; in both which parishes the usual numbers that died weekly were from four to six or eight, whereas at that time they were increased as follows: —

Besides this, it was observed, with great uneasiness by the people, that the weekly bills in general increased very much during these weeks, although it was at a time of the year when usually the bills are very moderate.

The usual number of burials within the bills of mortality for a week was from about two hundred and forty, or thereabouts, to three hundred. The last was esteemed a pretty high bill; but after this we found the bills successively increasing, as follows: —

This last bill was really frightful, being a higher number than had been known to have been buried in one week since the preceding visitation of 1656.

However, all this went off again; and the weather proving cold, and the frost, which began in December, still continuing very severe, even till near the end of February, attended with sharp though moderate winds, the bills decreased again, and the city grew healthy; and everybody began to look upon the danger as good as over, only that still the burials in St. Giles's continued high. From the beginning of April, especially, they stood at twenty-five each week, till the week from the 18th to the 25th, when there was13 buried in St. Giles's Parish thirty, whereof two of the plague, and eight of the spotted fever (which was looked upon as the same thing); likewise the number that died of the spotted fever in the whole increased, being eight the week before, and twelve the week above named.

This alarmed us all again; and terrible apprehensions were among the people, especially the weather being now changed and growing warm, and the summer being at hand. However, the next week there seemed to be some hopes again: the bills were low; the number of the dead in all was but 388; there was none of the plague, and but four of the spotted fever.

But the following week it returned again, and the distemper was spread into two or three other parishes, viz., St. Andrew's, Holborn, St. Clement's-Danes; and, to the great affliction of the city, one died within the walls, in the parish of St. Mary-Wool-Church, that is to say, in Bearbinder Lane, near Stocks Market: in all, there were nine of the plague, and six of the spotted fever. It was, however, upon inquiry, found that this Frenchman who died in Bearbinder Lane was one who, having lived in Longacre, near the infected houses, had removed for fear of the distemper, not knowing that he was already infected.

This was the beginning of May, yet the weather was temperate, variable, and cool enough, and people had still some hopes. That which encouraged them was, that the city was healthy. The whole ninety-seven parishes buried but fifty-four, and we began to hope, that, as it was chiefly among the people at that end of the town, it might go no farther; and the rather, because the next week, which was from the 9th of May to the 16th, there died but three, of which not one within the whole city or liberties;14 and St. Andrew's buried but fifteen, which was very low. It is true, St. Giles's buried two and thirty; but still, as there was but one of the plague, people began to be easy. The whole bill also was very low: for the week before, the bill was but three hundred and forty-seven; and the week above mentioned, but three hundred and forty-three. We continued in these hopes for a few days; but it was but for a few, for the people were no more to be deceived thus. They searched the houses, and found that the plague was really spread every way, and that many died of it every day; so that now all our extenuations15 abated, and it was no more to be concealed. Nay, it quickly appeared that the infection had spread itself beyond all hopes of abatement; that in the parish of St. Giles's it was gotten into several streets, and several families lay all sick together; and accordingly, in the weekly bill for the next week, the thing began to show itself. There was indeed but fourteen set down of the plague, but this was all knavery and collusion; for St. Giles's Parish, they buried forty in all, whereof it was certain most of them died of the plague, though they were set down of other distempers. And though the number of all the burials were16 not increased above thirty-two, and the whole bill being but three hundred and eighty-five, yet there was17 fourteen of the spotted fever, as well as fourteen of the plague; and we took it for granted, upon the whole, that there were fifty died that week of the plague.

The next bill was from the 23d of May to the 30th, when the number of the plague was seventeen; but the burials in St. Giles's were fifty-three, a frightful number, of whom they set down but nine of the plague. But on an examination more strictly by the justices of the peace, and at the lord mayor's18 request, it was found there were twenty more who were really dead of the plague in that parish, but had been set down of the spotted fever, or other distempers, besides others concealed.

But those were trifling things to what followed immediately after. For now the weather set in hot; and from the first week in June, the infection spread in a dreadful manner, and the bills rise19 high; the articles of the fever, spotted fever, and teeth, began to swell: for all that could conceal their distempers did it to prevent their neighbors shunning and refusing to converse with them, and also to prevent authority shutting up their houses, which, though it was not yet practiced, yet was threatened; and people were extremely terrified at the thoughts of it.

The second week in June, the parish of St. Giles's, where still the weight of the infection lay, buried one hundred and twenty, whereof, though the bills said but sixty-eight of the plague, everybody said there had been a hundred at least, calculating it from the usual number of funerals in that parish as above.

Till this week the city continued free, there having never any died except that one Frenchman, who20 I mentioned before, within the whole ninety-seven parishes. Now, there died four within the city, – one in Wood Street, one in Fenchurch Street, and two in Crooked Lane. Southwark was entirely free, having not one yet died on that side of the water.

I lived without Aldgate, about midway between Aldgate Church and Whitechapel Bars, on the left hand, or north side, of the street; and as the distemper had not reached to that side of the city, our neighborhood continued very easy. But at the other end of the town their consternation was very great; and the richer sort of people, especially the nobility and gentry from the west part of the city, thronged out of town, with their families and servants, in an unusual manner. And this was more particularly seen in Whitechapel; that is to say, the Broad Street where I lived. Indeed, nothing was to be seen but wagons and carts, with goods, women, servants, children, etc.; coaches filled with people of the better sort, and horsemen attending them, and all hurrying away; then empty wagons and carts appeared, and spare horses with servants, who it was apparent were returning, or sent from the country to fetch more people; besides innumerable numbers of men on horseback, some alone, others with servants, and, generally speaking, all loaded with baggage, and fitted out for traveling, as any one might perceive by their appearance.

This was a very terrible and melancholy thing to see, and as it was a sight which I could not but look on from morning to night (for indeed there was nothing else of moment to be seen), it filled me with very serious thoughts of the misery that was coming upon the city, and the unhappy condition of those that would be left in it.

This hurry of the people was such for some weeks, that there was no getting at the lord mayor's door without exceeding difficulty; there was such pressing and crowding there to get passes and certificates of health for such as traveled abroad; for, without these, there was no being admitted to pass through the towns upon the road, or to lodge in any inn. Now, as there had none died in the city for all this time, my lord mayor gave certificates of health without any difficulty to all those who lived in the ninety-seven parishes, and to those within the liberties too, for a while.

This hurry, I say, continued some weeks, that is to say, all the months of May and June; and the more because it was rumored that an order of the government was to be issued out, to place turnpikes21 and barriers on the road to prevent people's traveling; and that the towns on the road would not suffer people from London to pass, for fear of bringing the infection along with them, though neither of these rumors had any foundation but in the imagination, especially at first.

I now began to consider seriously with myself concerning my own case, and how I should dispose of myself; that is to say, whether I should resolve to stay in London, or shut up my house and flee, as many of my neighbors did. I have set this particular down so fully, because I know not but it may be of moment to those who come after me, if they come to be brought to the same distress and to the same manner of making their choice; and therefore I desire this account may pass with them rather for a direction to themselves to act by than a history of my actings, seeing it may not be of one farthing value to them to note what became of me.