Даниэль Дефо

The Storm

CHAPTER II

Of the Opinion of the Ancients, That this Island was more Subject to Storms than other Parts of the World

I am not of Opinion with the early Ages of the World, when these Islands were first known, that they were the most Terrible of any Part of the World for Storms and Tempests.

Cambden tells us, The Britains were distinguish'd from all the World by unpassable Seas and terrible Northern Winds, which made the Albion Shores dreadful to Sailors; and this part of the World was therefore reckoned the utmost Bounds of the Northern known Land, beyond which none had ever sailed: and quotes a great variety of ancient Authors to this purpose; some of which I present as a Specimen.

Et Penitus Toto Divisos Orbe Britannos.

Britain's disjoyn'd from all the well known World.

Quem Littus adusta,

Horrescit Lybiæ, ratibusq; Impervia *Thule *Taken frequently for Britain.

Ignotumq; Fretum.

Claud.

And if the Notions the World then had were true, it would be very absurd for us who live here to pretend Miracles in any Extremes of Tempests; since by what the Poets of those Ages flourish'd about stormy Weather, was the native and most proper Epithet of the Place:

Belluosus qui remotis

Obstrepit Oceanus Britannis.

Hor.

Nay, some are for placing the Nativity of the Winds hereabouts, as if they had been all generated here, and the Confluence of Matter had made this Island its General Rendezvouz.

But I shall easily show, that there are several Places in the World far better adapted to be the General Receptacle or Centre of Vapours, to supply a Fund of Tempestuous Matter, than England; as particularly the vast Lakes of North America: Of which afterwards.

And yet I have two Notions, one real, one imaginary, of the Reasons which gave the Ancients such terrible Apprehensions of this Part of the World; which of late we find as Habitable and Navigable as any of the rest.

The real Occasion I suppose thus: That before the Multitude and Industry of Inhabitants prevail'd to the managing, enclosing, and improving the Country, the vast Tract of Land in this Island which continually lay open to the Flux of the Sea, and to the Inundations of Land-Waters, were as so many standing Lakes; from whence the Sun continually exhaling vast quantities of moist Vapours, the Air could not but be continually crowded with all those Parts of necessary Matter to which we ascribe the Original of Winds, Rains, Storms, and the like.

He that is acquainted with the situation of England, and can reflect on the vast Quantities of flat Grounds, on the Banks of all our navigable Rivers, and the Shores of the Sea, which Lands at Least lying under Water every Spring-Tide, and being thereby continually full of moisture, were like a stagnated standing body of Water brooding Vapours in the Interval of the Tide, must own that at least a fifteenth part of the whole Island may come into this Denomination.

Let him that doubts the Truth of this, examine a little the Particulars; let him stand upon Shooters-Hill in Kent, and view the Mouth of the River Thames, and consider what a River it must be when none of the Marshes on either side were wall'd in from the Sea, and when the Sea without all question flow'd up to the Foot of the Hills on either Shore, and up every Creek, where he must allow is now dry Land on either side the River for two Miles in breadth at least, sometimes three or four, for above forty Miles on both sides the River.

Let him farther reflect, how all these Parts lay when, as our ancient Histories relate, the Danish Fleet came up almost to Hartford, so that all that Range of fresh Marshes which reach for twenty five Miles in length, from Ware to the River Thames, must be a Sea.

In short, Let any such considering Person imagine the vast Tract of Marsh-Lands on both sides the River Thames, to Harwich on the Essex side, and to Whitstable on the Kentish side, the Levels of Marshes up the Stour from Sandwich to Canterbury, the whole Extent of Lowgrounds commonly call'd Rumney-Marsh, from Hythe to Winchelsea, and up the Banks of the Rother; all which put together, and being allow'd to be in one place cover'd with Water, what a Lake wou'd it be suppos'd to make? According to the nicest Calculations I can make, it cou'd not amount to less than 500000 Acres of Land.

The Isle of Ely, with the Flats up the several Rivers from Yarmouth to Norwich, Beccles, &c. the continu'd Levels in the several Counties of Norfolk, Cambridge, Suffolk, Huntingdon, Northampton, and Lincoln, I believe do really contain as much Land as the whole County of Norfolk; and 'tis not many Ages since these Counties were universally one vast Moras or Lough, and the few solid parts wholly unapproachable: insomuch that the Town of Ely it self was a Receptacle for the Malecontents of the Nation, where no reasonable Force cou'd come near to dislodge them.

'Tis needless to reckon up twelve or fourteen like Places in England, as the Moores in Somersetshire, the Flat-shores in Lancashire, Yorkshire, and Durham, the like in Hampshire and Sussex; and in short, on the Banks of every Navigable River.

The sum of the matter is this; That while this Nation was thus full of standing Lakes, stagnated Waters, and moist Places, the multitude of Exhalations must furnish the Air with a quantity of Matter for Showers and Storms infinitely more than it can be now supply'd withal, those vast Tracts of Land being now fenc'd off, laid dry, and turn'd into wholsome and profitable Provinces.

This seems demonstrated from Ireland, where the multitude of Loughs, Lakes, Bogs, and moist Places, serve the Air with Exhalations, which give themselves back again in Showers, and make it be call'd, The Piss-pot of the World.

The imaginary Notion I have to advance on this Head, amounts only to a Reflection upon the Skill of those Ages in the Art of Navigation; which being far short of what it is since arrived to, made these vast Northern Seas too terrible for them to venture in: and accordingly, they rais'd those Apprehensions up to Fable, which began only in their want of Judgment.

The Phœnicians, who were our first Navigators, the Genoese, and after them the Portuguese, who arriv'd to extraordinary Proficiency in Sea Affairs, were yet all of them, as we say, Fair-weather Sea-men: The chief of their Navigation was Coasting; and if they were driven out of their Knowledge, had work enough to find their way home, and sometimes never found it at all; but one Sea convey'd them directly into the last Ocean, from whence no Navigation cou'd return them.

When these, by Adventures, or Misadventures rather, had at any time extended their Voyaging as far as this Island, which, by the way, they always perform'd round the Coast of Spain, Portugal, and France; if ever such a Vessel return'd, if ever the bold Navigator arriv'd at home, he had done enough to talk on all his Days, and needed no other Diversion among his Neighbours, than to give an Account of the vast Seas, mighty Rocks, deep Gulfs, and prodigious Storms he met with in these remote Parts of the known World: and this, magnified by the Poetical Arts of the Learned Men of those times, grew into a receiv'd Maxim of Navigation, That these Parts were so full of constant Tempests, Storms, and dangerous Seas, that 'twas present Death to come near them, and none but Madmen and Desperadoes could have any Business there, since they were Places where Ships never came, and Navigation was not proper in the Place.

And Thule, where no Passage was

For Ships their Sails to bear.

Horace has reference to this horrid Part of the World, as a Place full of terrible Monsters, and fit only for their Habitation, in the Words before quoted.

Belluosus qui remotis

Obstrepit Oceanus Britannis.

Juvenal follows his Steps;

Quanto Delphino Balæna Britannica major.

Juv.

Such horrid Apprehensions those Ages had of these Parts, which by our Experience, and the Prodigy to which Navigation in particular, and Sciential Knowledge in general, is since grown, appear very ridiculous.

For we find no Danger in our Shores, no uncertain wavering in our Tides, no frightful Gulfs, no horrid Monsters, but what the bold Mariner has made familiar to him. The Gulfs which frighted those early Sons of Neptune are search'd out by our Seamen, and made useful Bays, Roads, and Harbours of Safety. The Promontories which running out into the Sea gave them terrible Apprehensions of Danger, are our Safety, and make the Sailors Hearts glad, as they are the first Lands they make when they are coming Home from a long Voyage, or as they are a good shelter when in a Storm our Ships get under their Lee.

Our Shores are sounded, the Sands and Flats are discovered, which they knew little or nothing of, and in which more real Danger lies, than in all the frightful Stories they told us; useful Sea-marks and Land-figures are plac'd on the Shore, Buoys on the Water, Light-houses on the highest Rocks; and all these dreadful Parts of the World are become the Seat of Trade, and the Centre of Navigation: Art has reconcil'd all the Difficulties, and Use made all the Horribles and Terribles of those Ages become as natural and familiar as Day-light.

The Hidden Sands, almost the only real Dread of a Sailor, and by which till the Channels between them were found out, our Eastern Coast must be really unpassable, now serve to make Harbours: and Yarmouth Road was made a safe Place for Shipping by them. Nay, when Portsmouth, Plymouth, and other good Harbours would not defend our Ships in the Violent Tempest we are treating of, here was the least Damage done of any Place in England, considering the Number of Ships which lay at Anchor, and the Openness of the Place.

So that upon the whole it seems plain to me, that all the dismal things the Ancients told us of Britain, and her terrible Shores, arose from the Infancy of Marine Knowledge, and the Weakness of the Sailor's Courage.

Not but that I readily allow we are more subject to bad Weather and hard Gales of Wind than the Coasts of Spain, Italy, and Barbary. But if this be allow'd, our Improvement in the Art of Building Ships is so considerable, our Vessels are so prepar'd to ride out the most violent Storms, that the Fury of the Sea is the least thing our Sailors fear: Keep them but from a Lee Shore, or touching upon a Sand, they'll venture all the rest: and nothing is a greater satisfaction to them, if they have a Storm in view, than a sound Bottom and good Sea-room.

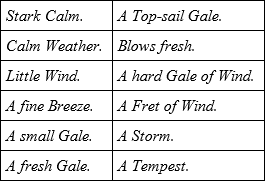

From hence it comes to pass, that such Winds as in those Days wou'd have pass'd for Storms, are called only a Fresh-gale, or Blowing hard. If it blows enough to fright a South Country Sailor, we laugh at it: and if our Sailors bald Terms were set down in a Table of Degrees, it will explain what we mean.

Just half these Tarpawlin Articles, I presume, would have pass'd in those Days for a Storm; and that our Sailors call a Top-sail Gale would have drove the Navigators of those Ages into Harbours: when our Sailors reef a Top-sail, they would have handed all their Sails; and when we go under a main Course, they would have run afore it for Life to the next Port they could make: when our Hard Gale blows, they would have cried a Tempest; and about the Fret of Wind they would be all at their Prayers.

And if we should reckon by this Account we are a stormy Country indeed, our Seas are no more Navigable now for such Sailors than they were then: If the Japoneses, the East Indians, and such like Navigators, were to come with their thin Cockleshell Barks and Calico Sails; if Cleopatra's Fleet, or Cæsar's great Ships with which he fought the Battle of Actium, were to come upon our Seas, there hardly comes a March or a September in twenty Years but would blow them to Pieces, and then the poor Remnant that got Home, would go and talk of a terrible Country where there's nothing but Storms and Tempests; when all the Matter is, the Weakness of their Shipping, and the Ignorance of their Sea-men: and I make no question but our Ships ride out many a worse Storm than that terrible Tempest which scatter'd Julius Cæsar's Fleet, or the same that drove Æneas on the Coast of Carthage.

And in more modern times we have a famous Instance in the Spanish Armada; which, after it was rather frighted than damag'd by Sir Francis Drake's Machines, not then known by the Name of Fireships, were scatter'd by a terrible Storm, and lost upon every Shore.

The Case is plain, 'Twas all owing to the Accident of Navigation: They had, no doubt, a hard Gale of Wind, and perhaps a Storm; but they were also on an Enemy's Coast, their Pilots out of their Knowledge, no Harbour to run into, and an Enemy a-stern, that when once they separated, Fear drove them from one Danger to another, and away they went to the Northward, where they had nothing but God's Mercy, and the Winds and Seas to help them. In all those Storms and Distresses which ruin'd that Fleet, we do not find an Account of the Loss of one Ship, either of the English or Dutch; the Queen's Fleet rode it out in the Downs, which all Men know is none of the best Roads in the World; and the Dutch rode among the Flats of the Flemish Coast, while the vast Galleons, not so well fitted for the Weather, were forc'd to keep the Sea, and were driven to and fro till they had got out of their Knowledge; and like Men desperate, embrac'd every Danger they came near.

This long Digression I could not but think needful, in order to clear up the Case, having never met with any thing on this Head before: At the same time 'tis allow'd, and Histories are full of the Particulars, that we have often very high Winds, and sometimes violent Tempests in these Northen Parts of the World; but I am still of opinion, such a Tempest never happen'd before as that which is the Subject of these Sheets: and I refer the Reader to the Particulars.

CHAPTER III

Of the Storm in General

Before we come to examine the Damage suffer'd by this terrible Night, and give a particular Relation of its dismal Effects; 'tis necessary to give a summary Account of the thing it self, with all its affrightning Circumstances.

It had blown exceeding hard, as I have already observ'd, for about fourteen Days past; and that so hard, that we thought it terrible Weather: Several Stacks of Chimnies were blown down, and several Ships were lost, and the Tiles in many Places were blown off from the Houses; and the nearer it came to the fatal 26th of November, the Tempestuousness of the Weather encreas'd.

On the Wednesday Morning before, being the 24th of November, it was fair Weather, and blew hard; but not so as to give any Apprehensions, till about 4 a Clock in the Afternoon the Wind encreased, and with Squauls of Rain and terrible Gusts blew very furiously.

The Collector of these Sheets narrowly escap'd the Mischief of a Part of a House, which fell on the Evening of that Day by the Violence of the Wind; and abundance of Tiles were blown off the Houses that Night: the Wind continued with unusual Violence all the next Day and Night; and had not the Great Storm follow'd so soon, this had pass'd for a great Wind.

On Friday Morning it continued to blow exceeding hard, but not so as that it gave any Apprehensions of Danger within Doors; towards Night it encreased: and about 10 a Clock, our Barometers inform'd us that the Night would be very tempestuous; the Mercury sunk lower than ever I had observ'd it on any Occasion whatsoever, which made me suppose the Tube had been handled and disturb'd by the Children.

But as my Observations of this Nature are not regular enough to supply the Reader with a full Information, the Disorders of that dreadful Night having found me other Imployment, expecting every Moment when the House I was in would bury us all in its own Ruins; I have therefore subjoin'd a Letter from an Ingenious Gentleman on this very Head, directed to the Royal Society, and printed in the Philosophical Transactions, No. 289. P. 1530. as follows.

A Letter from the Reverend Mr. William Derham, F.R.S. Containing his Observations concerning the late Storm

SIR,

According to my Promise at the general Meeting of the R.S. on St. Andrews Day, I here send you inclos'd the Account of my Ingenious and Inquisitive Friend Richard Townely, Esq; concerning the State of the Atmosphere in that Part of Lancashire where he liveth, in the late dismal Storm. And I hope it will not be unaccepable, to accompany his with my own Observations at Upminster; especially since I shall not weary you with a long History of the Devastations, &c. but rather some Particulars of a more Philosophical Consideration.

And first, I do not think it improper to look back to the preceding Seasons of the Year. I scarce believe I shall go out of the way, to reflect as far back as April, May, June and July; because all these were wet Months in our Southern Parts. In April there fell 12,49 l. of Rain through my Tunnel: And about 6, 7, 8, or 9, l. I esteem a moderate quantity for Upminster. In May there fell more than in any Month of any Year since the Year 1696, viz. 20,77 l. June likewise was a dripping Month, in which fell 14,55 l. And July, although it had considerable Intermissions, yet had 14,19 l. above 11 l. of which fell on July 28th and 29th in violent Showers. And I remember the News Papers gave Accounts of great Rains that Month from divers Places of Europe; but the North of England (which also escaped the Violence of the late Storm) was not so remarkably wet in any of those Months; at least not in that great proportion more than we, as usually they are; as I guess from the Tables of Rain, with which Mr. Towneley hath favoured me. Particularly July was a dry Month with them, there being no more than 3,65 l. of Rain fell through Mr. Towneley's Tunnel of the same Diameter with mine.

From these Months let us pass to September, and that we shall find to have been a wet Month, especially the latter part of it; there fell of Rain in that Month, 14,86 l.

October and November last, although not remarkably wet, yet have been open warm Months for the most part. My Thermometer (whose freezing Point is about 84) hath been very seldom below 100 all this Winter, and especially in November.

Thus I have laid before you as short Account as I could of the preceding Disposition of the Year, particularly as to wet and warmth, because I am of opinion that these had a great Influence in the late Storm; not only in causing a Repletion of Vapours in the Atmosphere, but also in raising such Nitro-sulphureous or other heterogeneous matter, which when mix'd together might make a sort of Explosion (like fired Gun-powder) in the Atmosphere. And from this Explosion I judge those Corruscations or Flashes in the Storm to have proceeded, which most People as well as my self observed, and which some took for Lightning. But these things I leave to better Judgments, such as that very ingenious Member of our Society, who hath undertaken the Province of the late Tempest; to whom, if you please, you may impart these Papers; Mr. Halley you know I mean.

From Preliminaries it is time to proceed nearer to the Tempest it self. And the foregoing Day, viz. Thursday, Nov. 25. I think deserveth regard. In the Morning of that day was a little Rain, the Winds high in the Afternoon: S.b.E. and S. In the Evening there was Lightning; and between 9 and 10 of the Clock at Night, a violent, but short Storm of Wind, and much Rain at Upminster; and of Hail in some other Places, which did some Damage: There fell in that Storm 1,65 l. of Rain. The next Morning, which was Friday, Novem. 26. the Wind was S.S.W. and high all Day, and so continued till I was in Bed and asleep. About 12 that Night, the Storm awaken'd me, which gradually encreas'd till near 3 that Morning; and from thence till near 7 it continued in the greatest excess: and then began slowly to abate, and the Mercury to rise swiftly. The Barometer I found at 12 h. ½ P.M. at 28,72, where it continued till about 6 the next Morning, or 6¼, and then hastily rose; so that it was gotten to 82 about 8 of the Clock, as in the Table.

How the Wind sat during the late Storm I cannot positively say, it being excessively dark all the while, and my Vane blown down also, when I could have seen: But by Information from Millers, and others that were forc'd to venture abroad; and by my own guess, I imagin it to have blown about S.W. by S. or nearer to the S. in the beginning, and to veer about towards the West towards the End of the Storm, as far as W.S.W.

The degrees of the Wind's Strength being not measurable (that I know of, though talk'd of) but by guess, I thus determine, with respect to other Storms. On Feb. 7. 1698/9. was a terrible Storm that did much damage. This I number 10 degrees; the Wind then W.N.W. vid. Ph. Tr. No. 262. Another remarkable Storm was Feb. 3. 1701/2. at which time was the greatest descent of the ☿ ever known: This I number 9 degrees. But this last of November, I number at least 15 degrees.

As to the Stations of the Barometer, you have Mr. Towneley's and mine in the following Table to be seen at one View.

A Table shewing the Height of the Mercury in the Barometer, at Townely and Upminster, before, in, and after the Storm

As to November 17th (whereon Mr. Towneley mentions a violent Storm in Oxfordshire) it was a Stormy Afternoon here at Upminster, accompanied with Rain, but not violent, nor ☿ very low. November 11th and 12th had both higher Winds and more Rain; and the ☿ was those Days lower than even in the last Storm of November 26th.

Thus, Sir, I have given you the truest Account I can, of what I thought most to deserve Observation, both before, and in the late Storm. I could have added some other particulars, but that I fear I have already made my Letter long, and am tedious. I shall therefore only add, that I have Accounts of the Violence of the Storm at Norwich, Beccles, Sudbury, Colchester, Rochford, and several other intermediate places; but I need not tell Particulars, because I question not but you have better Informations.

Thus far Mr. Derham's Letter

It did not blow so hard till Twelve a Clock at Night, but that most Families went to Bed; though many of them not without some Concern at the terrible Wind, which then blew: But about One, or at least by Two a Clock, 'tis suppos'd, few People, that were capable of any Sense of Danger, were so hardy as to lie in Bed. And the Fury of the Tempest encreased to such a Degree, that as the Editor of this Account being in London, and conversing with the People the next Days, understood, most People expected the Fall of their Houses.

And yet in this general Apprehension, no body durst quit their tottering Habitations; for whatever the Danger was within doors, 'twas worse without; the Bricks, Tiles, and Stones, from the Tops of the Houses, flew with such force, and so thick in the Streets, that no one thought fit to venture out, tho' their Houses were near demolish'd within.

The Author of this Relation was in a well-built brick House in the skirts of the City; and a Stack of Chimneys falling in upon the next Houses, gave the House such a Shock, that they thought it was just coming down upon their Heads: but opening the Door to attempt an Escape into a Garden, the Danger was so apparent, that they all thought fit to surrender to the Disposal of Almighty Providence, and expect their Graves in the Ruins of the House, rather than to meet most certain Destruction in the open Garden: for unless they cou'd have gone above two hundred Yards from any Building, there had been no Security, for the Force of the Wind blew the Tiles point-blank, tho' their weight inclines them downward: and in several very broad Streets, we saw the Windows broken by the flying of Tile-sherds from the other side: and where there was room for them to fly, the Author of this has seen Tiles blown from a House above thirty or forty Yards, and stuck from five to eight Inches into the solid Earth. Pieces of Timber, Iron, and Sheets of Lead, have from higher Buildings been blown much farther; as in the Particulars hereafter will appear.

It is the receiv'd Opinion of abundance of People, that they felt, during the impetuous fury of the Wind, several Movements of the Earth; and we have several Letters which affirm it: But as an Earthquake must have been so general, that every body must have discern'd it; and as the People were in their Houses when they imagin'd they felt it, the Shaking and Terror of which might deceive their Imagination, and impose upon their Judgment; I shall not venture to affirm it was so: And being resolv'd to use so much Caution in this Relation as to transmit nothing to Posterity without authentick Vouchers, and such Testimony as no reasonable Man will dispute; so if any Relation come in our way, which may afford us a Probability, tho' it may be related for the sake of its Strangeness or Novelty, it shall nevertheless come in the Company of all its Uncertainties, and the Reader left to judge of its Truth: for this Account had not been undertaken, but with design to undeceive the World in false Relations, and to give an Account back'd with such Authorities, as that the Credit of it shou'd admit of no Disputes.

For this reason I cannot venture to affirm that there was any such thing as an Earthquake; but the Concern and Consternation of all People was so great, that I cannot wonder at their imagining several things which were not, any more than their enlarging on things that were, since nothing is more frequent, than for Fear to double every Object, and impose upon the Understanding, strong Apprehensions being apt very often to perswade us of the Reality of such things which we have no other reasons to shew for the probability of, than what are grounded in those Fears which prevail at that juncture.

Others thought they heard it thunder. 'Tis confess'd, the Wind by its unusual Violence made such a noise in the Air as had a resemblance to Thunder; and 'twas observ'd, the roaring had a Voice as much louder than usual, as the Fury of the Wind was greater than was ever known: the Noise had also something in it more formidable; it sounded aloft, and roar'd not very much unlike remote Thunder.

And yet tho' I cannot remember to have heard it thunder, or that I saw any Lightning, or heard of any that did in or near London; yet in the Counties the Air was seen full of Meteors and vaporous Fires: and in some places both Thundrings and unusual Flashes of Lightning, to the great terror of the Inhabitants.

And yet I cannot but observe here, how fearless such People as are addicted to Wickedness, are both of God's Judgments and uncommon Prodigies; which is visible in this Particular, That a Gang of hardned Rogues assaulted a Family at Poplar, in the very Height of the Storm, broke into the House, and robb'd them: it is observable, that the People cryed Thieves, and after that cryed Fire, in hopes to raise the Neighbourhood, and to get some Assistance; but such is the Power of Self-Preservation, and such was the Fear, the Minds of the People were possess'd with, that no Body would venture out to the Assistance of the distressed Family, who were rifled and plundered in the middle of all the Extremity of the Tempest.

It would admit of a large Comment here, and perhaps not very unprofitable, to examine from what sad Defect in Principle it must be that Men can be so destitute of all manner of Regard to invisible and superiour Power, to be acting one of the vilest Parts of a Villain, while infinite Power was threatning the whole World with Disolation, and Multitudes of People expected the Last Day was at Hand.

Several Women in the City of London who were in Travail, or who fell into Travail by the Fright of the Storm, were oblig'd to run the risque of being delivered with such Help as they had; and Midwives found their own Lives in such Danger, that few of them thought themselves oblig'd to shew any Concern for the Lives of others.

Fire was the only Mischief that did not happen to make the Night compleatly dreadful; and yet that was not so every where, for in Norfolk the Town of – was almost ruin'd by a furious Fire, which burnt with such Vehemence, and was so fann'd by the Tempest, that the Inhabitants had no Power to concern themselves in the extinguishing it; the Wind blew the Flames, together with the Ruines, so about, that there was no standing near it; for if the People came to Windward they were in Danger to be blown into the Flames; and if to Leeward the Flames were so blown up in their Faces, they could not bear to come near it.

If this Disaster had happen'd in London, it must have been very fatal; for as no regular Application could have been made for the extinguishing it, so the very People in Danger would have had no Opportunity to have sav'd their Goods, and hardly their Lives: for though a Man will run any Risque to avoid being burnt, yet it must have been next to a Miracle, if any Person so oblig'd to escape from the Flames had escap'd being knock'd on the Head in the Streets; for the Bricks and Tiles flew about like small Shot; and 'twas a miserable Sight, in the Morning after the Storm, to see the Streets covered with Tyle-sherds, and Heaps of Rubbish, from the Tops of the Houses, lying almost at every Door.

From Two of the Clock the Storm continued, and encreased till Five in the Morning; and from Five, to half an Hour after Six, it blew with the greatest Violence: the Fury of it was so exceeding great for that particular Hour and half, that if it had not abated as it did, nothing could have stood its Violence much longer.

In this last Part of the Time the greatest Part of the Damage was done: Several Ships that rode it out till now, gave up all; for no Anchor could hold. Even the Ships in the River of Thames were all blown away from their Moorings, and from Execution-Dock to Lime-House Hole there was but our Ships that rid it out, the rest were driven down into the Bite, as the Sailors call it, from Bell-Wharf to Lime-House; where they were huddeld together and drove on Shore, Heads and Sterns, one upon another, in such a manner, as any one would have thought it had been impossible: and the Damage done on that Account was incredible.