Дмитрий Емец

Mutiny of the Little Sweeties

Translated from Russian by Jane H. Buckingham

Translation edited by Shona Brandt

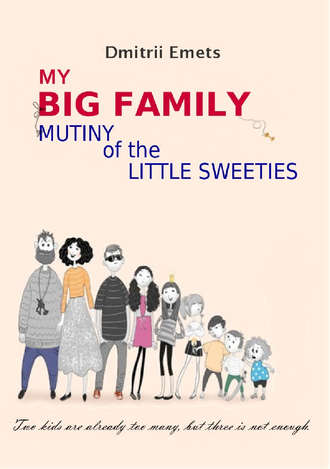

Illustrations by Viktoria Timofeeva

Chapter One

It All Begins

Two kids are already too many, but three is not enough.

A well-known fact

In the city of Moscow in a two-bedroom apartment lived the Gavrilov family. The family consisted of a father, a mother, and seven children.

Papa’s name was Nicholas. He wrote fiction and was afraid to even step briefly away from the computer so that the small children would not type any extraneous characters into the text. Nevertheless, characters were still okay. It was much worse when the children managed to delete a piece of text accidentally, and Papa discovered it only a month later, when he started to edit the book.

Still, they pestered Papa all the time because he worked at home, and when a person works at home, it seems to everyone that he is always free. Therefore, Papa got up at four in the morning, slipped into the kitchen with the laptop, and froze when he heard children’s feet starting to thump on the floor in the next room. This meant that he had not managed to get out of the room unnoticed and now one or two whining kids would be hanging around him.

Mama’s name was Anna. She worked in the library centre as the senior skilled hand in the Skilful Hands circle. True, she frequently stayed home because she had given birth to another child. At one time, Mama even had an online store of educational games and school supplies. The store was on the glassed-in balcony. There it resided on the many shelves that Papa knocked together, hitting his own fingers with the hammer. The children really liked that they had their own store. And they liked it even more when Mama gathered the orders in the big room, laying out dozens of different interesting games on the carpet.

They then sat and said to each other, “The main thing is not to touch anything!” At this time, the older ones held the younger ones’ hands just in case. The younger ones either bit, because it is not very agreeable when someone holds you back, or were filled with a sense of responsibility and also taught each other, “The main thing is to put everything in its place!” and “The main thing is if you opened the package, then close it carefully!”

However, all the same, if Mama had gone for a short while to put away the milk or answer the phone, packages would go out to the customers with incorrectly-sorted blocks, with gnawed-through mosaics, or entirely without chips. One client received Papa’s sneaker in the box and was about as unhappy as Papa. The client and Papa then had a long phone call and arranged where to meet to return the sneaker, but never met. About six months later, Papa made off with the second sneaker from one of the kids or Mama, and everyone denounced him in one voice.

Besides children, skilful hands, and games, Mama was also the family ingester. As soon as she had some free time, she immediately ate up everything from the children’s plates and slept. “Don’t bug me!” she declared.

Peter, the oldest of the Gavrilov children, was 15. He talked mysteriously with someone on the phone for days on end, leaping onto the landing where only five floors of neighbours could hear him, did his homework late at night, and at home fenced himself off from his brothers and sisters with furniture, on which he hung “Do Not Enter!” signs. He wrote in school questionnaires that he was an only child in the family and he walked on the street away from everybody so no one would think that this whole crowd was related to him.

For all that, when the younger children sometimes went to Grandma for a week, Peter was obviously bored. He walked around the empty apartment, looked under the bed and said pensively, “How quiet, for some reason! When will they come back? Soon now?”

His sister Vicky was 13. She could not sit at the table while there was at least one crumb on it. She could not lie down in bed if the sheet had not been ironed to the point that the last wrinkle had disappeared. Still, Vicky constantly danced by herself and in principle read only those books with horses. For example, there are horses in War and Peace, so she read War and Peace. There are no horses in Woe from Wit,[1] so Woe from Wit remained forever unread, even if the teacher hanged herself on the blinds. Never mind that Woe from Wit is seven times shorter and five times easier.

Vicky always did her homework with great care and suffered for half an hour when a line was coming up to the margin but she still had three letters or numbers. It would be stupid to carry over to a new line, but you would have to climb over the margin to finish it!

Mama and Papa never stopped wondering how Vicky managed to combine in herself the romantic, the love of horses, all these wrinkles on the sheets, the agony because of the climb over the margin, and the crumbs on the table.

Kate recently turned 11. She had the nickname of Catherine the Great. She was the only one of all the children who knew the password of the “big computer” and her brothers and sisters had to beg her to turn it on. “Why? Have you done your homework? Washed your hands? Put away your things? When did you last brush your teeth?” Kate asked sternly, after which the convicted, screaming “oh-oh-oh” with tears of impatience in the eyes, raced hurriedly to choke down kasha or brush their teeth.

Once, Papa got tired of this and removed the password from the computer altogether. But it just got worse. The children fought, each wanted to watch or do his own thing on the computer, and the little ones generally spent so much time in front of the monitor that they fell from their chairs. Therefore, it was necessary to return to the system of Kate’s despotism, and again everything was calm.

When she was free from active management, Kate always went through the apartment and put up yellow stickies with the notices: Don’t steal chairs! Put them back when done! or Toys should promptly be put away before 7 p.m.!

Alena was eight. She was constantly falling in love, and this surprised her sisters, because Kate and Vicky, though older, rarely fell in love. Alena was nicknamed the “No Girl.” If she was asked to do something, she immediately shouted, “No! Never! Nothing doing!” and would instantly do it. But if others responded, “Yes, now!” then they would have to wait three hours. Therefore, it turned out that the No Girl helped with the young ones more than everyone.

Six-year-old Alex was a great chemist. He mixed everything with anything and watched what happened. For example, he mixed shoe polish with apple juice, squirted deodorant in there, and checked if it would explode or not. Food from the fridge, especially flour and eggs, and liquid from the top shelves in the bathroom suffered the most from Alex’s experiments. One day he accidentally discovered that vinegar and soda could make a big boom if they were mixed correctly. From then on, vinegar and soda almost had to be taped to the ceiling, because he was forever stealing them. Alex modestly described his talent as follows: “Now my name is Superpower! Now my name is Megamind![2] Now my name is Flying Rag!”

Four-year-old Costa’s left hand did not work too well and he limped a little. Although the limping did not even prevent him from running, the hand had to be worked constantly, which was the cause of Mama’s eternal worry. Knowing that he could not rely on his left hand, Costa walked around with a wooden sword all the time and was an expert at head butting. Alex and Costa could exist peacefully for no more than five minutes a day. Even in the car, they could not sit next to each other but only with a child between them. Knowing the hardness of Costa’s head, Alex was afraid to fight him and preferred to blast his brother from a distance or fire from a slingshot. Each time it usually ended with Alex hitting Costa in the eye with a small block and hiding under the sofa from his wrath, and Costa furiously pounding on the sofa with his sword and shouting, “Ah! Kill him on the butt!”

Rita recently turned two. She was not talking very well yet, but she was always eating and was very round. A first breakfast, a second breakfast, a third breakfast, and then it was already time for lunch. If you hid food from her, Rita would steal the soap from the bathroom and nibble at its edge. She also constantly wanted those things that were in the hands of her brothers and sisters. Pencil case, backpack, textbook, it did not matter what it was. She would stage wild concerts to get them. Hence, the other kids were forever devising ways to outwit her. They would take some sock or unwanted head from a doll and pretend not to give it to her for anything. Rita would stage a concert, receive the doll’s head, and run off to hide it. And everyone could do homework in peace.

When such a large family went for a stroll, people exclaimed. Different people, especially the elderly, often came up to them and asked, “Are these all yours?”

“Yes, they’re ours,” Papa and Mama cautiously replied.

At home, the children slept on bunk beds, forming three sides of a rectangle; in addition, the younger ones had cribs with a removable side panel. When the side panel was removed, the crib could be placed right up against the parents’ bed and the young one could roll in and roll out like a round loaf.

However, despite all the tricks, the Gavrilovs settled themselves rather poorly in the two-room apartment. The bathroom was always busy, the bathroom door was constantly taken off the hinges, and their relations with the neighbours in the same entrance were cool. It was probably due to the internal walls, which were very thin and sounds passed through easily. The majority of the neighbours more or less understood the situation, but on the second floor lived a lonely old woman who was forever tormented by the suspicion that the children were sawing with a blunt saw at night.

“Why did they shout like that in the middle of the night?”

“Because Rita wanted to go to the store and the other children tried to soothe her,” Mama patiently explained.

“You’re the parents! Explain to her that stores don’t open in the middle of the night!”

“We did, but she only believed it when we drove her to the store and showed her that it was indeed closed!”

“I don’t like all this! I’ll be watching!” the old granny said, turning pale.

“Well, watch for yourself!” Mama gave her permission, but her mood was spoilt all the same.

Mama went from room to room and begged the children to speak in a whisper. The older kids more or less agreed with her, but the younger ones did not quite know how to whisper.

“Mama, I whispered correctly yesterday, right?” one of them yelled from the bathroom, through closed door.

Mama grabbed her head, and Papa said, “You know, I thought I understood the meaning of the word ‘horde’!”

“What?”

“Are you sure I should clarify?”

The watchful granny was very annoying. She had no idea that, under different names and with different appearances, she had become a popular character in contemporary literature. Papa, not knowing how to take revenge on her, killed her in many novels. Three times fiery dragons burned the watchful granny. Twice hungry goblins ate her. Once the murder took place in the elevator and the criminal managed to hide the body without a trace as the elevator went from the fifth to the third floor.

Somehow, when the children got noisy once again, the watchful granny called the police about “underground production at home.” Three police officers in bulletproof vests with assault rifles came to expose the operation. First, they plugged up the hallway all at once and started to feel out something, but Mama declared that there would be nothing for them to feel out, because one child was sitting on the potty and the other would soon be waking up. Then Alex appeared and began to ask the police for an assault rifle. He said that he would not shoot and only wanted to look at the bullets. The police did not give him a rifle, but while an officer was rescuing his weapon from Alex, the rifle barrel got entangled in the tab of his mesh jacket and it was difficult to extricate because the hallway was terribly tight. While all three officers were disentangling one rifle, Costa appeared, triumphantly carrying in front of him the potty with the results of his efforts, then Rita woke up, and the police began to back out very slowly to the stairs.

“What do you produce here at least?” one, the youngest, asked hopelessly.

“You still don’t understand? Come on, go, go!” the older officer said and began to push him back down the stairs.

However, the absence of an underground factory in the apartment did not improve relations with the watchful granny. Peter even drew a caricature very similar to her, under which in bold letters was the caption: I WATCH, I AM WATCHING, I WILL BE WATCHING!

The watchful granny continued to irritate them, though no one was walking on tiptoe anymore anyway. One day Mama sat on the floor in the hallway, crying, and said, “I can’t take it anymore!”

“What’s ‘it’?” Papa was puzzled, looking out from the kitchen with the laptop, where he was dealing with the watchful neighbour once again, sending her live piranhas in a jar with cucumbers.

“We’re too crowded here! We’re like sardines in a can! This city has eaten me up!” Mama repeated and cried even louder.

Then Papa and Mama began to dream about moving to a detached house by the sea, where there would be no neighbours, and renting out the apartment in the big city. They weighed, considered, and decided to take a chance.

“Good thing that you don’t have to work!” Mama said.

“What?! I work from morning to night, but the kids interrupt me all the time!” Papa was outraged.

“That’s right! In a house, you’ll have your own office! We’ll all walk on tiptoe and not disturb you!”

“Yes!” Papa Gavrilov was inspired. “A real office with a real desk! I’ll wind barbed wire with an electrical current around the door and put wolf traps near it. In addition, there’ll be holes in the door through which you can spit out poison darts.”

Chapter Two

Papa Searches for a House

Papa, did you buy worms? Did you buy food for the worms? But what will they eat?

©Alex

In March, Papa Gavrilov went to the sea and began searching for a house that they could rent for a long time. The seaside town had low buildings, very picturesque, with roofs lined with red clay tiles. Leaves had not yet appeared everywhere, but many trees had already blossomed, and their soft pink flowers became blurred in the eyes, so that one could not see individual flowers. It seemed like the trees were wrapped in a luminous cloud.

Papa had a list of addresses, but, alas, it seemed that everything depicted on the Internet was not quite as in reality. What was presented as “a detached house with many rooms” turned out to be a cramped temporary shed in the owner’s yard divided by plywood partitions, and with windows looking out at a howling dog on a chain. What really looked more or less like a house cost so much that it did not suit Papa.

Wandering around town until the evening, Papa despaired. He decided to take the train and leave. However, there was still a lot of time until the train, and he sat down to rest in a confusing lane similar to the figure 8. Two entrances led into this lane, but they were very narrow and, if one did not know them, it was possible to go endlessly along the “eight” which never ended.

Papa sat on the curb near mailboxes, where there was a board and a jar with cigarette butts, and began to eat a sausage. Soon a large shaggy dog approached him, barking carefully, and calmly sat down. After a minute, a medium-sized dog of off-white colour came running, also barked at Papa, and sat down with a sense of having fulfilled its duty. Last, with a front leg drawn in, a small but very long dog with a bald back walked up, also barked, and took a seat beside the first two. It was felt that all three dogs had known each other for a long time but did not know Papa, and they were interested. Papa fed the dogs some sausage and waited for a fourth dog, because someone else was barking close by.

However, a fourth dog did not appear, but a dried-up grandpa about eighty came out of a gate instead. He stopped nearby and began to look quietly at Papa. Papa at first did not understand why the grandpa was standing there, but then surmised that it was his board and his jar with cigarette butts. Papa, apologizing, moved over, and the grandpa sat down beside him. They got into conversation and Papa told him that he was searching for a house but could find nothing and was therefore going to the station. The grandpa muttered something and then they were already chatting about something else.

Papa Gavrilov finished eating the sausage and went to the station. The station was quiet. Direct trains only came here in the summer, when resort visitors were travelling, and the rest of the time, only six cars were coupled to a longer train at the railway junction.

There was still a lot of time till the train, the car doors were not open, and Papa strolled along the platform. Suddenly he heard someone hailing him. He looked around and saw the dried-up grandpa, making his way to him, hurrying and breathless.

“I was thinking! I’ll rent my house!” the grandpa said.

“And you?” Papa asked.

“I’ve intended for a long time to go to my granddaughter. But she lives far away in Yekaterinburg. I won’t be able to come here, but I don’t want to abandon the house, because it’s indeed home and has to constantly do something with it. I need the proper person whom I could trust. Are you the proper fellow?”

Papa said that he did not know if he was the proper person.

“But you won’t sell the kitchen table? You won’t unscrew the sockets?”

Papa promised that he would not sell the table, but some of the young ones might just unscrew the sockets. Or shove clay or paper clips in them. But Papa did not mention this, and they went to see the grandpa’s house.

Papa really liked the house, although it was not detached but semi-detached. It had two floors with a large attic and its own separate plot of land in a shape resembling the letter L. The long arm was the size of three cars and the short arm of one car. There was even a tree on the plot – a huge old walnut.

On the ground floor were one large room, one small room, and the kitchen. On the second were three small rooms and one medium one. The sea was not visible from the window, but the lighthouse standing on the seashore was.

“Does it work?” Papa asked.

“Of course! The searchlight turns at night. I lived here for forty-two years with my wife and now seven years without her. I played the trumpet in a military orchestra. We bought the house here when my wife said that she had bad lungs and needed warm winters,” the grandpa said and stroked the windowsill, as if it was alive.

“Then maybe you shouldn’t…” Papa began, but the old man hastily repeated that he had decided everything a long time ago; it was dangerous for him to live alone because he had trouble with his heart from time to time, and he was very glad that everything was finally taking shape.

They agreed on how much to pay and on how to send money, and the grandpa began to show where the fuse box was, where the meters were, how to shut off the water, and what bad habits the gas boiler had.

“It’s good, this boiler, better than other new ones, but a little stubborn. Need to get a feel for it. It lights with matches, here… Only when you light it, keep your face away!”

Papa looked suspiciously sideways at the boiler. It looked like a huge cannon projectile, and tubes of different diameters were connected to it. Something was puffing and raging in the boiler.

“Any instructions for it?” Papa specified timidly.

“What instructions? It’s almost the same age as me. The main thing is just be friendly to it,” the old man said, sighing, and began to twist a big valve. “Here, I turned it off! Now I’ll light it! Careful!”

The old man held a match up to the boiler, and – PUFF!

It was the loudest “puff” in the world. Papa even squatted, saving his head just in case, but the boiler was already peacefully heating water, and an extremely satisfied old man stood beside it.

“Well, that’s all! Seems I’ve shown you everything! Now run for the train!” he hurried Papa and Papa travelled to Mama and the children.

* * *

April and May went in a terrible rush. They advertised the Moscow apartment with an agency and rented it to a family with two children, which would take possession in June. The children of this family were so quiet that Papa was certain the watchful neighbour would like them. Although, possibly she would now decide that the tenants’ children sat quietly because the parents gagged them or tied them to chairs.

“Not a sound for an hour! Just sat and drew with markers! Why can’t ours be so docile!” Mama said enviously.

“Ours can’t, but others can. It seems to me that ours are Italian spies,” Papa responded.

“You and I are Italian spies! Only the Italians don’t know about it yet,” Mama added.

She had barely slept in recent weeks. No one knew when she rested. Since the beginning of May, Mama had been packing what they would take with them and giving away what they would not take at all.

During these two months, the dried-up grandpa changed his mind three times about going to his granddaughter, and then made up his mind again. This confused Papa, but all the same, Mama persisted in continuing packing, declaring that she had already made up her mind, and once she did, it was then too late to give up. Whatever happened, they would just go and sit on the bags at the station, and then somehow everything would work out by itself.

Then the grandpa raised the price slightly and went to his granddaughter after all. This took place a few days before the end of the last school term. The children would start in a new school in a new town in the new school year. Now everyone realized that the journey was actually happening and started to pack four times faster.

Each child packed his own things in his own backpack. The younger had a smaller backpack, the older, a bigger one, with the exception of Rita, who was so little that her backpack was a frog with a zipper at the mouth.

Alex assembled a full backpack of toys, and when they did not fit into it, he started banging on the backpack with a hammer, kneading it so that it turned out to be more compact. At the same time, by way of selfless help, he also “kneaded” with the hammer the big bag in which Mama had packed the dishes, after which it turned out that all the dishes left whole could easily fit in one package.

“Well, doesn’t matter!” Mama said, consoling herself. “Indeed, we could break them on the road, and then it would be much more annoying!”

Kate filled her whole backpack with animal cages. At the bottom was the cage with a guinea pig, then a rat cage on it, and at the top of the pyramid – the red-eared slider turtle Mafia. They named the turtle Mafia because, when it was living in the aquarium, it ate newts, crayfish, and goldfish. It gobbled up absolutely everything at night without a trace, but during the day, it stayed at the bottom like a completely respectable individual, so they started to suspect it only because the newts, crayfish, and goldfish simply could not have just gotten up and gone somewhere on business. Later Kate suddenly remembered that they were not going yet and pulled out all the cages so that the animals would not suffocate. Nevertheless, having pulled out the cages, Kate again succumbed to the mood of general packing and put everything back. She again thought that they would suffocate and again pulled them out.

Alena whined and did not want to go anywhere. She had fallen in love with Vadik from the next class, who always threw a heavy medicine ball at her back during physical education, but never at the other girls. Although there were bruises from the ball on her back, it was still not worth ignoring Vadik.

Kate, the older sister, interrogated Alena, “Vadik! Ha! What was the name of the boy you fell in love with last week? Dima?”

“Cyril. He stuck gum in my hair.”

“But Dima didn’t?”

“Cyril also stuck gum in Dima’s hair.”

Kate twirled a finger at her temple. “Ugh! Such drama! Cyril and Dima stick gum in each other’s hair, and she falls in love with some unfortunate Vadik! That’s it, go pack your backpack!”

Alena took a broom, swept her broken heart away into the dustpan, and started packing.

Finally, the day of departure arrived. Papa took Mama and the kids to the station. Then he was to return, load into the minivan the things that amounted to much more than seven backpacks, and drive for a whole day. However, the train also took a day. So they should turn up in the same place around the same time.

The watchful granny from the second floor unexpectedly went to see them off at the station. Papa and Mama did not want to take her at all and made up a story about broken seatbelts in the third row of seats, but it turned out to be quite difficult to turn her down. In the car, the old woman held Rita on her lap and kissed the top of her head, and Rita turned her head, because the kiss was moist.

“Look! She’s drinking from her brain!” Peter whispered and laughed so wildly that they wanted to send him to the station by subway.

At the station, the old woman kissed all the children, not even excluding Peter, who had to bend down because he was two heads taller. Peter, after being kissed, made scary faces and tried to catch free Wi-Fi at the station.

“I remember when you were still so tiny!” the old woman said, showing with her hand the level of her knee. Then she gave the children a transistor radio with a solar charger. Rita, of course, immediately wanted the radio for herself alone and she lay down on the asphalt right on the platform so that everyone could see how indispensable it was to her.

“It will be shared! And it’s yours too!” Kate said, but Rita wanted it only for herself and kicked.

“Look here! No one is torturing her!” Papa Gavrilov could not refrain from saying.

“Work with the child’s character, work! Explain to her!” the watchful granny said, but in a rather weak voice.

The train started moving and the watchful granny waved to them. “Kate, Alex, Rita, Costa, Vicky, Alena, Peter! Goodbye! Write me! I don’t even know your address!” she shouted.

Mama was astonished. She had not even suspected that the watchful granny knew all their children by name. The train pulled away, and it was visible from the window that the neighbour was walking along the platform and wiping her eyes.

“You know, but she’s kind of good! How come we didn’t notice this before?” Mama said uncertainly.

“We can go back! It’s not too late to jump off the train!” Vicky proposed.

“No! We won’t go back!” Mama hastily replied. “But now that I know she’s good, my heart will be lighter!”

Vicky chuckled and sat down to read The Headless Horseman,[3] in which there were often horses.