Маргарет Митчелл

Gone with the Wind / Унесённые ветром

Part two

Chapter VIII

As the train carried Scarlett northward that May morning in 1862, she remembered what Gerald had told her when she was a child. The fact was that she and Atlanta were christened in the same year. It had had different names before, and not until the year of Scarlett’s birth had it become Atlanta.

When Gerald first moved to north Georgia, there had been no Atlanta at all, not even a village. But the next year, in 1836, the State had authorized the building of a railroad through the territory which the Cherokees[26] had recently left.

The people who settled the town were a pushy people. Restless, energetic people from Georgia and more distant states were drawn to this town by the railroads. They came with enthusiasm. They built their stores around the muddy red roads. They built their fine homes where Indian feet had beaten a path[27]called the Peachtree Trail. They were proud of the place, proud of its growth, proud of themselves for making it grow.

Scarlett stood on the lower step of the train, a pale pretty figure in her black mourning dress. She hesitated, unwilling to soil her slippers, and looked about for Miss Pittypat. There was no sign of her, but soon Scarlett saw an old negro, who came toward her through the mud, his hat in his hand.

“Dis Miss Scarlett, ain’ it? Dis hyah Peter, Miss Pitty’s coachman. Doan step down in dat mud,” he ordered, as Scarlett gathered up her skirts. “Lemme cahy you.”

He picked Scarlett up with ease. As he was carrying her toward the carriage, she recalled what Charles had said about Uncle Peter: “He went through all the Mexican campaigns with Father, nursed him when he was wounded – in fact, he saved his life. Uncle Peter practically raised Melanie and me, for we were very young when Father and Mother died. He was the one who decided I should have a larger allowance when I was fifteen, and he insisted that I should go to Harvard. He’s the smartest old darky I’ve ever seen and about the most devoted.”

When Uncle Peter finally maneuvered the carriage out of the mudholes and onto Peachtree Street, she noticed how the town had grown in a year! It did not seem possible that the little Atlanta she knew could have changed so much.

For the past year, Atlanta had been transformed. It was humming like a beehive, proudly conscious of its importance to the Confederacy. There were factories turning out machinery to manufacture war materials. There were strange faces on the streets of Atlanta now. One could hear foreign tongues of Europeans who had run the blockade[28] to have made pistols, rifles, cannon and powder for the Confederacy. Trains roared in and out of the town at all hours.

Here along Peachtree Street and near-by streets were the headquarters of the various army departments, each office swarming with uniformed men. Scarlett felt that Atlanta must be a city of the wounded, for there were general hospitals without number. And every day the trains brought more sick and more wounded.

There was an exciting atmosphere about the place that uplifted her. It was as if she could actually feel the pulse of the town’s heart beating in time with her own.

The sidewalks were crowded with men in uniform; the narrow street was jammed with vehicles – carriages, buggies, ambulances; convalescents limped about on crutches; and Scarlett had her first sight of Yankee uniforms, as Uncle Peter pointed to a detachment of bluecoats going toward the depot to entrain for the prison camp.

“Oh,” thought Scarlett, with a feeling of real pleasure, “I’m going to like it here! It’s so alive and exciting!”

The town was even more alive than she realized, for there were new barrooms by the dozens; prostitutes, following the army, filled the town and bawdy houses were blossoming with women. There were parties and balls and bazaars every week and war weddings without number.

As they progressed down the street, Scarlett asked a lot of questions and Peter answered them, pointing here and there with his whip, proud to display his knowledge.

Now Uncle Peter pointed to three ladies and bowed. These ladies were Mrs. Merriwether, Mrs. Whiting, and Mrs. Elsing – the pillars of Atlanta. They ran the three churches to which they belonged. They organized bazaars and presided over sewing circles, they arranged balls and picnics, they knew who made good matches and who did not, who drank secretly, who were to have babies and when. But in fact, these three ladies heartily disliked and distrusted one another.

The carriage stopped for a moment to permit two ladies with baskets of bandages to cross the street on stepping stones. At the same moment, Scarlett’s eye was caught by a figure on the sidewalk in a brightly colored dress – too bright for street wear. Turning she saw a tall handsome woman with a bold face and a mass of red hair. She watched her, fascinated.

“Uncle Peter, who is that?” she whispered.

“Ah doan know.”

“You do, too. I can tell. Who is she?”

“Her name Belle Watling,” said Uncle Peter.

Scarlett was quick to catch the fact that he had not said “Miss” or “Mrs.”

“Who is she?”

“Miss Scarlett,” said Peter darkly, laying the whip on the horse, “Miss Pitty ain’ gwine ter lak it you astin’ questions dat ain’ none of yo’ bizness.”

“Good Heavens!” thought Scarlett. “That must be a bad woman!”

She had never seen a bad woman before and she twisted her head and stared after her until she was lost in the crowd.

Finally the business section was behind and the residences came into view. As they passed a green clapboard house, Dr. Meade and his wife came out, calling greetings. Scarlett recalled that they had been at her wedding. The doctor went through the mud to the side of the carriage. He was tall and gaunt, and his clothes hung on his figure. Atlanta considered him the root of all strength and all wisdom. But for all his pompous manner, he was a very kind man.

After shaking Scarlett’s hand, the doctor announced that Aunt Pittypat had promised that she should be on Mrs. Meade’s hospital and bandage-rolling committee.

“What are hospital committees anyway?”

Both the doctor and his wife looked shocked at her ignorance.

“But, of course, you’ve been buried in the country and couldn’t know,” Mrs. Meade apologized for her. “We have nursing committees for different hospitals and for different days. We nurse the men and help the doctors and make bandages and clothes and when the men are well enough to leave the hospitals we take them into our homes till they are able to go back in the army. Dr. Meade is at the Institute hospital where my committee works, and everyone says he’s marvelous and —”

“There, there, Mrs. Meade,” said the doctor fondly. “Don’t go bragging on me in front of folks.”

Uncle Peter cleared his throat.

“Miss Pitty were in a state when Ah lef’ home an’ ef Ah doan git dar soon, she’ll done fainted.”

“Good-by. I’ll be over this afternoon,” called Mrs. Meade. “And you tell Pitty for me that if you aren’t on my committee, she’s going to be in a worse state.”

The houses were farther apart now, and leaning out Scarlett saw the red brick and slate roof of Miss Pittypat’s house. It was almost the last house on the north side of town. On the front steps stood two women in black. They were Miss Pittypat and Melanie. And Scarlett realized that the fly in the ointment [29]of Atlanta would be this slight little person in black dress and a loving smile of welcome and happiness on her heart-shaped face.

When a Southerner packed a trunk and traveled twenty miles for a visit, the visit was seldom of shorter duration than a month, usually much longer. Southerners were as enthusiastic visitors as they were hosts, and there was nothing unusual in relatives coming to spend the Christmas holidays and remaining until July. Visitors added excitement and variety to the slow-moving Southern life and they were always welcome.

So Scarlett had come to Atlanta with no idea as to how long she would remain. If her stay was pleasant, she would remain indefinitely. But as soon as she had arrived, Aunt Pitty and Melanie began a campaign to make her home permanently with them. They brought up every possible argument. They were lonely and often frightened at night in the big house, and she was so brave she gave them courage. She was so charming that she cheered them in their sorrow. Now that Charles was dead, her place was with his relatives. Besides, half the house now belonged to her, through Charles’ will. Last, the Confederacy needed every pair of hands for sewing, knitting, bandage rolling and nursing the wounded.

Charles’ Uncle Henry Hamilton, who lived in bachelor state at the Atlanta Hotel near the depot, also talked seriously to her on this subject. He liked Scarlett immediately because, he said, he could see that she had sense. He was trustee, not only of Pitty’s and Melanie’s estates, but also of that left Scarlett by Charles. It came to Scarlett as a pleasant surprise that she was now a well-to-do young woman, for Charles had not only left her half of Aunt Pitty’s house but farm lands and town property as well. And the stores and warehouses along the railroad track near the depot, which were part of her inheritance, had tripled in value since the war began.

As for Uncle Peter, he took it for granted[30] that Scarlett had come to stay. To all these arguments, Scarlett smiled but said nothing, as now that she was away from Tara, she missed it very much. For the first time, she realized what Gerald had meant when he said that the love of the land was in her blood.

Gradually, Scarlett came back to herself, and almost before she realized it her spirits rose to normal. She was only seventeen, she had superb health and energy, and Charles’ people did their best to make her happy. They not only admired her high-spirits, her figure, her tiny hands and feet, her white skin, but they said so frequently, petting, hugging and kissing her to emphasize their loving words.

Scarlett basked in the compliments. No one at Tara had ever said so many charming things about her.

All in all, life went on as happily as was possible under the circumstances. Atlanta was more interesting than Savannah or Charleston or Tara and it offered so many strange war-time occupations she had little time to think or mope. But, sometimes, when she blew out the candle, she sighed and thought: “If only Ashley wasn’t married! If only I didn’t have to nurse in that hospital! Oh, if only I could have some beaux!”

She had immediately hated nursing but she could not escape this duty because she was on both Mrs. Meade’s and Mrs. Merriwether’s committees. And they would have been shocked to know how slight an interest in the war she had. Four mornings a week she spent in the sweltering, stinking hospital. Except for the ever-present worry that Ashley might be killed, the war interested her not at all, and nursing was something she did simply because she didn’t know how to get out of it.

Certainly there was nothing romantic about nursing. To her, it meant groans, delirium, death and smells.

Melanie, however, did not seem to mind the smells or the wounds. And where the wounded could see her, she was gentle, sympathetic and cheerful, and the men in the hospitals called her an angel of mercy[31].

On three afternoons a week Scarlett had to attend sewing circles and bandage-rolling committees of Melanie’s friends. The girls who had all known Charles were very kind to her at these gatherings but treated her, as if she were old and finished. How unfair that everyone should think her heart was in the grave when it wasn’t at all! It was in Virginia with Ashley!

But in spite of these discomforts, Atlanta pleased her very well. And her visit lengthened as the weeks went by.

Chapter IX

Scarlett sat in the window of her bedroom that midsummer morning and watched the wagons and carriages full of girls, soldiers and chaperons ride gaily out Peachtree road in search of decorations for the bazaar which was to be held that evening for the benefit of the hospitals. Girls in flowered cotton dresses, elderly ladies smiling in carriages, convalescents from the hospitals, officers on horseback – everybody was going to have a picnic. Everybody, thought Scarlett, sadly, except me.

It simply wasn’t fair. She had worked twice as hard as any girl in town, getting things ready for the bazaar. She had knitted socks and afghans and mufflers. And she had embroidered half a dozen sofa-pillow cases with the Confederate flag on them. Yesterday she had worked until she was worn out. Under the supervision of the Committee, this was hard work and no fun at all. Oh, it wasn’t fair that she should have a dead husband and be out of everything that was pleasant. She tried not to smile and wave too enthusiastically to the men she knew best, but it was hard to hide her dimples, hard to look as though her heart were in the grave – when it wasn’t.

Pittypat entered the room and jerked her away from the window unceremoniously.

“Have you lost your mind, honey, waving at men out of your bedroom window? I declare, Scarlett, I’m shocked! What would your mother say?”

“Well, they didn’t know it was my bedroom.”

“Honey, you mustn’t do things like that. Everybody will be talking about you and saying you are fast.”

“Well, I’m sorry, Auntie! I forgot it was my bedroom window.

I won’t do it again – I – I just wanted to see them go by. I wish I was going.”

“Honey!”

“Well, I do. I’m so tired of sitting at home.”

“Scarlett, promise me you won’t say things like that. People would talk so. They’d say you didn’t have the proper respect for poor Charlie —”

“Oh, Auntie, don’t cry!” And Scarlett wailed out loud – not, as Pittypat thought, for poor Charlie but because the last sounds of the wheels and the laughter were dying away.

“Oh, now I’ve made you cry, too,” sobbed Pittypat, in a pleased way, fumbling for her handkerchief.

Melanie came running from her room: “Darlings! What is the matter?”

“Charlie!” sobbed Pittypat.

“Oh,” said Melly, “Be brave, dear. Don’t cry. Oh, Scarlett!”

Scarlett had thrown herself on the bed and was sobbing at the top of her voice, sobbing for her lost youth and the pleasures of youth.

“I might as well be dead!” she sobbed passionately.

“Dear, don’t cry! Try to think how much Charlie loved you and let that comfort you!”

“Oh, do go away and leave me alone!”

She sank her face into the pillow, and the two standing over her tiptoed out. She heard Melanie say to Pittypat:

“Aunt Pitty, I wish you wouldn’t speak of Charles to her. You know how it always affects her. We mustn’t make it harder for her.”

Scarlett kicked the coverlet in impotent rage.

She remained gloomily in her room until afternoon and then the sight of the returning picnickers did not cheer her. Life was a hopeless affair and certainly not worth living.

Good riddance came in the form she least expected when, during the after-dinner-nap period, Mrs. Merriwether and Mrs. Elsing drove up.

“Mrs. Bonnell’s children have the measles,” said Mrs. Merriwether abruptly.

“And the McLure girls have been called to Virginia,” said Mrs. Elsing, “for Dallas McLure is wounded.”

“So, Pitty, we need you and Melly tonight to take Mrs. Bonnell’s and the McLure girls’ places,” said Mrs. Merriwether.

“Oh, we just couldn’t – with poor Charlie dead only a —”

“I know how you feel but there isn’t any sacrifice too great for the Cause,” broke in Mrs. Elsing.

“I think we should go,” said Scarlett. “It is the least we can do for the hospital.”

Neither of the visiting ladies had even mentioned her name, and they turned and looked sharply at her. Scarlett’s face kept a childlike expression.

“I think we should go and help to make it a success, all of us. I think I should go in the booth with Melly because – well, I think it would look better for us both. Don’t you think so, Melly?”

“Well,” began Melly helplessly. The idea of appearing publicly at a social gathering while in mourning was so unheard of she was bewildered.

“Scarlett’s right,” said Mrs. Merriwether. “And I know Charlie would like you to help the Cause he died for.”

“Too good to be true![32]” said Scarlett’s joyful heart. Actually she was at a party! After a year’s seclusion, she was at the biggest party Atlanta had ever seen. And she could see people and many lights and hear music.

She sat down on one of the little stools behind the counter of the booth and looked up and down the long hall. It looked lovely. And everywhere among the greenery, on flags, blazed the bright stars of the Confederacy.

The musicians got on the platform, black, grinning, their fat cheeks already shining with sweat, and began tuning their fiddles. Scarlett felt her heart beat faster as the sweet melancholy of the waltz came to her:

“The years creep slowly by, Lorena! The snow is on the grass again. The sun’s far down the sky, Lorena…”

One-two-three, one-two-three. What a beautiful waltz!

Suddenly the hall burst into life. It was full of girls, who floated in bright dresses; round little white shoulders bare; lace shawls carelessly hanging from arms; girls with masses of golden curls about their necks.

There were so many uniforms in the crowd on so many men whom Scarlett knew, men she had met on hospital cots, on the streets, at the drill ground. All of them were so young looking, so handsome, so reckless, with their arms in slings, with head bandages white across sun-browned faces. Some of them were on crutches and how proud were the girls who slowed their steps to their escorts’ hopping pace! The whole hospital must have turned out, at least everybody who could walk. The hospital should make a lot of money tonight.

There was a sound of drums from the street below, the tramp of feet. In a moment, the Home Guard and the militia unit in their bright uniforms crowded into the room, bowing, saluting, shaking hands.

The orchestra burst into “Bonnie Blue Flag[33].”

A hundred voices took it up, sang it, shouted it like a cheer.

“Hurrah! Hurrah! For the Southern Rights, hurrah! Hurrah for the Bonnie Blue Flag that bears a single star!”

They started the second verse and Scarlett, singing with the rest, heard the high sweet soprano of Melanie behind her. Turning, she saw that Melly was standing with her hands clasped to her breast, her eyes closed, and tiny tears oozing from the corners. She smiled at Scarlett, as the music ended.

“I’m so happy,” she whispered, “and so proud of the soldiers that I just can’t help crying about it.”

The same look was on the faces of all the women as the song ended, tears of pride on cheeks, pink or wrinkled, smiles on lips, as they turned to their men, sweetheart to lover, mother to son, wife to husband. They were all beautiful with the beauty that transfigures even the plainest woman when she is utterly protected and loved and is giving back that love a thousand times.

They loved their men, they believed in them, they trusted them to the last breaths of their bodies. It was devotion to and pride in the Confederacy, for final victory was at hand. Stonewall Jackson[34]’s triumphs in the Valley and the defeat of the Yankees in the Seven Days’ Battle around Richmond showed that clearly. How could it be otherwise with such leaders as Lee[35] and Jackson? One more victory and the Yankees would be on their knees asking for peace and the men would be riding home and there would be kissing and laughter. One more victory and the war was over!

But then Scarlett’s joy began to evaporate as she didn’t feel any such emotion. It bewildered and depressed her. Somehow, the ball did not seem so pretty nor the girls so dashing, and the devotion to the Cause – why, it just seemed silly!

The Cause didn’t seem sacred to her. The war didn’t seem to be a holy affair, but a nuisance that killed men and cost money and made luxuries hard to get. She saw that she was tired of the endless knitting and the endless bandage rolling. And oh, she was so tired of the hospital! Tired and bored and nauseated with the sickening gangrene smells and the endless moaning, frightened by the look of coming death.

Oh, why was she different? She could never love anything or anyone so selflessly as they did. She was trying to justify herself to herself – a task which she seldom found difficult.

The other women were simply silly and hysterical with their talk of patriotism and the Cause, and the men were almost as bad with their talk of States’ Rights. She, Scarlett O’Hara Hamilton, alone had good hard-headed Irish sense. She wasn’t going to make a fool out of herself about the Cause, but neither was she going to make a fool out of herself by admitting her true feelings. She was hard-headed enough to be practical about the situation, and no one would ever know how she felt.

She looked about the hall with distaste. The McLure girls’ booth was inconspicuous and there were long intervals when no one came to their corner and Scarlett had nothing to do but look enviously on the happy crowd.

No, she was not happy now as just being present was not enough. She was at the bazaar but not a part of it. No one paid her any attention. And all her life she had enjoyed the center of the stage. It wasn’t fair! She was seventeen years old and her feet were patting the floor, wanting to dance.

Every girl in Atlanta could have a man. Even the plainest girls were carrying on like belles – and, oh, worst of all, they were wearing such lovely, lovely dresses!

Here she sat like a crow with black taffeta to her wrists and buttoned up to her chin, watching tacky-looking girls hanging on the arms of good-looking men. All because Charles Hamilton had had the measles. He didn’t even die in battle, so she could brag about him.

She leaned her elbows on the counter and looked at the crowd.

For a brief moment she considered the unfairness of it all. How short was the time for fun, for pretty clothes, for dancing, for coquetting! Only a few, too few years! Then you married and wore dull-colored dresses and only emerged to dance with your husband or with old gentlemen who stepped on your feet. If you didn’t do these things, the other matrons talked about you and then your reputation was ruined and your family disgraced.

How wonderful it would be never to marry but to go on being lovely in pale green dresses and forever courted by handsome men. But, if you went on too long, you got to be an old maid and everyone said “poor thing” in that hateful way. No, after all it was better to marry and keep your self-respect even if you never had any more fun.

Oh, what a mess life was! Why had she been such an idiot as to marry Charles of all people and have her life end at sixteen?

There were crowds in front of every other counter but theirs, girls chattering, men buying. The few who came to them talked about how they went to the university with Ashley and what a fine soldier he was or spoke in respectful tones of Charles and how great a loss to Atlanta his death had been.

Then the music broke into the sounds of “Johnny Booker, he’p dis Nigger!” and Scarlett thought she would scream. She wanted to dance. She looked across the floor and tapped her foot to the music and her green eyes blazed eagerly. All the way across the floor, a man, newly come and standing in the doorway, saw them and started in recognition. Then he grinned to himself as he recognized the invitation that any male could read.

He was a tall man, towering over the officers who stood near him. And he stared at Scarlett, until finally, feeling his gaze, she looked toward him.

Somewhere in her mind, the bell of recognition rang[36], but for the moment she could not recall who he was. But he was the first man in months who had displayed an interest in her, and she threw him a gay smile. Suddenly, she knew who he was.

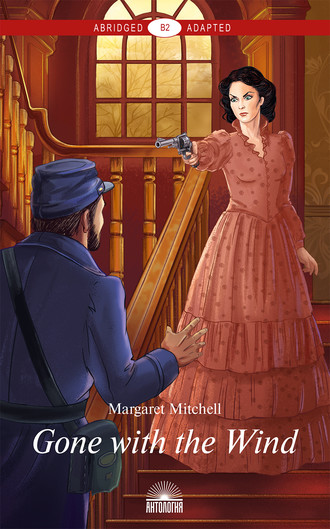

Thunderstruck, she stood as if paralyzed while he made his way through the crowd. Then, she tried to run away, but her skirt caught on a nail of the booth. She jerked furiously at it, tearing it and, in an instant, he was beside her.

“Permit me,” he said bending over. “I hardly hoped that you would recall me, Miss O’Hara.”

His voice was oddly pleasant to the ear. She looked up at him, her face red with the shame of their last meeting, and met his eyes, dancing in merciless merriment. Of all the people in the world to turn up here, this terrible person who had witnessed that scene with Ashley, who had said, and with good cause, that she was not a lady.

At the sound of his voice, Melanie turned and for the first time in her life Scarlett thanked God for the existence of her sister-in-law.

“Why – it’s – it’s Mr. Rhett Butler, isn’t it?” said Melanie with a little smile, putting out her hand. “I met you —”

“On the happy occasion of the announcement of your engagement,” he finished, bending over her hand. “It is kind of you to recall me.”

“And what are you doing so far from Charleston, Mr. Butler?”

“A boring matter of business, Mrs. Wilkes. I will be in and out of your town from now on[37]. I find I must not only bring in goods but supervise the use of them.”

“Bring in —” Melly broke into a delighted smile. “Why, you – you must be the famous Captain Butler we’ve been hearing so much about – the blockade runner. Why, every girl here is wearing dresses you brought in. Scarlett, aren’t you excited – what’s the matter, dear? Are you faint? Do sit down.”

Scarlett sank to the stool. Oh, what a terrible thing to happen! She had never thought to meet this man again. He took her black fan from the counter and began fanning her, his face grave but his eyes still dancing.

“It is quite warm in here,” he said. “No wonder Miss O’Hara is faint. May I lead you to a window?”

“No,” said Scarlett, so rudely that Melly stared.

“She is not Miss O’Hara any longer,” said Melly. “She is Mrs. Hamilton. She is my sister now.”

“Your husbands are here tonight, I trust, on this happy occasion? It would be a pleasure to renew acquaintances.”

“My husband is in Virginia,” said Melly with a proud lift of her head. “But Charles —” Her voice broke.

“He died in camp,” said Scarlett flatly. Would this creature never go away? Melly looked at her, startled.

“My dear ladies – how could I! You must forgive me. But permit a stranger to say that to die for one’s country is to live forever.”

Melanie smiled at him through tears. Again he had made a graceful remark, but he did not mean a word of it. He was jeering at Scarlett. He knew she hadn’t loved Charles. And Melly was just a big enough fool not to see through him. Abruptly she snatched the fan from his hand.

“I’m quite all right,” she said. “There’s no need to blow my hair out of place.”

“Scarlett, darling! Captain Butler, you must forgive her. She – she isn’t herself when she hears poor Charlie’s name spoken – and perhaps, after all, we shouldn’t have come here tonight. We’re still in mourning, you see, and it’s quite a strain on her – all this gaiety and music, poor child.”

“I quite understand,” he said, but as he turned to Melanie, his expression changed, respect coming over his dark face. “I think you’re a courageous little lady, Mrs. Wilkes.”

“Not a word about me!” thought Scarlett indignantly, as Melly smiled in confusion. Then she turned to three cavalrymen who appeared at her counter. For a moment, Melanie thought how nice Captain Butler was. Then she forgot about him, as more customers crowded to her.

“Your husband has been dead long?”

“Oh, yes, a long time. Almost a year.”

“And this is your first social appearance?”

“I know it looks quite odd,” she explained rapidly. “But the McLure girls who were to take this booth were called away and there was no one else, so Melanie and I —”

“No sacrifice is too great for the Cause.”

“I think you are horrid,” she said, dropping her eyes.

He leaned down across the counter until his mouth was near her ear and hissed: “Fear not, fair lady! Your guilty secret is safe with me!”

“Oh,” she whispered, “how can you say such things!”

“I only thought to ease your mind. What would you have me say? ‘Be mine, beautiful female, or I will reveal all?’”

She met his eyes and saw they were as teasing as a small boy’s. Suddenly she laughed. It was such a silly situation, after all. He laughed too, and so loudly that several of the chaperons in the corner looked their way.

There was a roll of drums and many voices cried “Sh!” as Dr. Meade mounted the platform and spread out his arms for quiet.

“We must all give grateful thanks to the charming ladies whose patriotic efforts have made this bazaar a success.”

Everyone clapped approvingly.

“The ladies have given their best, not only of their time but of the labor of their hands, and these beautiful objects in the booths are doubly beautiful, made as they are by the fair hands of our charming Southern women.”

There were more shouts of approval.

“But these things are not enough. We must have more money to buy medical supplies from England, and we have with us tonight the brave captain who has so successfully run the blockade for a year and who will run it again to bring us the drugs we need. Captain Rhett Butler!”

There was a loud burst of applause as he bowed and a craning of necks from the ladies in the corner. So that was who poor Charles Hamilton’s widow was carrying on with! And Charlie hardly dead a year!

“We need more gold and I am asking you for it,” the doctor continued. “I am asking a sacrifice but a sacrifice so small compared with the sacrifices our gallant men in gray are making that it will seem laughably small. Ladies, the Confederacy wants your jewelry, and I know no one will hold back.”

Scarlett’s first thought was one of deep thankfulness that mourning forbade her wearing her precious earbobs and the heavy gold chain that had been Grandma Robillard’s. She saw women, old and young, laughing, tugging at bracelets, earrings, helping each other undo necklace clasps, unpinning brooches from bosoms. As a man with the basket passed Rhett Butler, a handsome gold cigar case was thrown carelessly into it. When he came to Scarlett and rested his basket upon the counter, she shook her head to show that she had nothing to give. It was embarrassing to be the only person present who was giving nothing. And then she saw the bright gleam of her wide gold wedding ring.