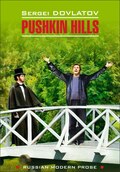

Сергей Довлатов

The Suitcase / Чемодан. Книга для чтения на английском языке

© Antonina W. Bouis, 2013

© Издательство КАРО, 2020

But even like this, my Russia,

You are most precious to me…

Alexander Blok[1]

Foreword

So this bitch at OVIR[2] says to me, “Everyone who leaves is allowed three suitcases. That’s the quota. Aspecial regulation of the ministry.”

No point in arguing. But of course I argued. “Only three suitcases? What am I supposed to do with all my things?”

“Like what?”

“Like my collection of race cars.”

“Sell them,” the clerk said, without lifting her head.

Then, knitting her brows[3] slightly, she added, “If you’re dissatisfied with something, write a complaint.”

“I’m satisfied,” I said.

After prison, everything satisfied me.

“Well, then, don’t make trouble…”

A week later I was packing. As it turned out, I needed just a single suitcase.

I almost wept with self-pity. After all, I was thirty-six years old. Had worked eighteen of them. I earned money, bought things with it. I owned a certain amount, it seemed to me. And still I only needed one suitcase – and of rather modest dimensions at that. Was I poor, then? How had that happened?

Books? Well, basically, I had banned books, which were not allowed through customs anyway. I had to give them out to my friends, along with my so-called archives.

Manuscripts? I had clandestinely sent them to the West a long time before.

Furniture? I had taken my desk to the secondhand store. The chairs were taken by the artist Chegin, who had been making do with[4] crates. The rest I threw out.

And so I left the Soviet Union with one suitcase. It was plywood, covered with fabric and, had chrome reinforcements at the corners. The lock didn’t work; I had to wind clothes line[5] around it.

Once I had taken it to Pioneer camp. It said in ink on the lid: “Junior group. Seryozha Dovlatov.” Next to it someone had amiably scratched: “Shithead”. The fabric was torn in several places. Inside, the lid was plastered with photographs: Rocky Marciano, Louis Armstrong, Joseph Brodsky, Gina Lollobrigida[6] in a transparent outfit. The customs agent tried to tear Lollobrigida off with his nails. He succeeded only in scratching her. But he didn’t touch Brodsky. He merely asked, “Who’s that?” I said he was a distant relative…

On May 16 I found myself in Italy. I stayed in the Hotel Dina in Rome. I shoved the suitcase under the bed.

I soon received fees from Russian journals. I bought blue sandals, flannel slacks and four linen shirts. I never opened the suitcase.

Three months later I moved to the United States, to New York. First I lived in the Hotel Rio. Then we stayed with friends in Flushing. Finally, I rented an apartment in a decent neighbourhood. I put the suitcase in the back of the closet. I never undid the clothes line.

Four years passed. Our family was reunited. Our daughter turned into a young American. Our son was born. He grew up and started misbehaving. One day my wife, exasperated, shouted, “Into the closet, right now!”

He spent about three minutes in there. I let him out and asked, “Were you scared? Did you cry?”

He said, “No. I sat on the suitcase.”

Then I took out the suitcase. And opened it.

On top was a decent double-breasted suit, intended for interviews, symposiums, lectures and fancy receptions. I figured it would do for Nobel ceremonies, too. Then a poplin[7] shirt and shoes wrapped in paper. Beneath them, a corduroy jacket lined with fake fur. To the left, a winter hat of fake sealskin. Three pairs of Finnish nylon crêpe[8] socks. Driving gloves. And last but not least, an officer’s leather belt.

On the bottom of the suitcase lay a page of Pravda from May 1980. A large headline proclaimed: “LONG LIVE THE GREAT TEACHING!” From the middle of the page stared a portrait of Karl Marx[9].

As a schoolboy I liked to draw the leaders of the world proletariat – especially Marx. Just start smearing an ordinary splotch of ink around and you’ve already got a resemblance…

I looked at the empty suitcase. On the bottom was Karl Marx. On the lid was Brodsky. And between them, my lost, precious, only life.

I shut the suitcase. Mothballs rattled around inside. The clothes were piled up in a motley mound on the kitchen table. That was all I had acquired in thirty-six years. In my entire life in my homeland. I thought, “Could this be it?” And I replied, “Yes, this is it.”

At that point, memories engulfed me. They must have been hidden in the folds of those pathetic rags, and now they had escaped. Memories that should be called From Marx to Brodsky. Or perhaps, What I Acquired. Or simply, The Suitcase.

But, as usual, this foreword is beginning to drag.

The Finnish Crêpe Socks

This happened eighteen years ago, when I was a student at Leningrad University.

The university campus was in the old part of town. The combination of water and stone creates a special, majestic atmosphere there. It’s hard to be a slacker under those circumstances, but I managed.

Since there is such a thing as the exact sciences, there must also be the inexact sciences. It seems to me that first among the inexact sciences is philology. And so I became a student in the philology department.

A week later a slender girl in imported shoes fell in love with me. Her name was Asya. Asya introduced me to her friends. They were all older than us – engineers, journalists, cameramen. One was even a store manager. These people dressed well. They liked going to restaurants and travelling. Some had their own cars.

Back then they seemed mysterious, powerful and attractive. I wanted to belong to their crowd. Later many of them emigrated. Now they’re just regular elderly Jews.

The life we led demanded significant expenditures. Most often they fell on the shoulders of Asya’s friends. This embarrassed me considerably. I still remember how Dr Logovinsky slipped me four roubles while Asya was hailing a cab[10] …

You can divide the world into two kinds of people: those who ask, and those who answer. Those who pose questions, and those who frown in irritation in response.

Asya’s friends did not ask her questions. And all I ever did was ask, “Where were you? Who did you meet in the subway? Where did you get that French perfume?”

Most people consider problems whose solutions don’t suit them to be insoluble. And they constantly ask questions to which they don’t need truthful answers.

To cut a long story short, I was meddlesome and stupid.

I acquired debts. They grew in geometric progression. By November they had reached eighteen roubles – a monstrous sum in those days. I learnt about pawnshops with their stubs and receipts, their atmosphere of dejection and poverty.

When Asya was near I couldn’t think about it. But as soon as we said goodbye, the thought of my debts floated in like a black cloud. I awoke with a sense of impending disaster. It took me hours just to convince myself to get dressed. I seriously planned holding up a jewellery store. I was convinced that all the thoughts of a pauper in love were criminal.

By then my academic success had diminished noticeably. Asya hadn’t been an outstanding student to begin with. The deans began talking about our moral image. I noticed that when a man is in love and he has debts, his moral image becomes a topic of conversation.

In short, everything was horrible.

Once I was wandering around town looking for six roubles. I had to get my winter coat out of hock. And I ran into[11] Fred Kolesnikov.

Fred was smoking, leaning against the brass rail of the Eliseyev Store. I knew he was a black marketeer[12]. Asya had introduced us once. He was a tall young man, about twenty-three years old, with an unhealthy complexion. As he spoke, he smoothed his hair nervously.

Without a second thought, I went over to him. “Could you lend me six roubles until tomorrow?” I tried to act pushy when I borrowed money, so that people could turn me down easily.

“Without a doubt,” said Fred, taking out a small, square wallet.

I regretted not asking for more.

“Take more,” said Fred.

Like a fool, I protested.

Fred looked at me curiously.

“Let’s have lunch,” he said. “My treat.”

His demeanour was simple and natural. I always envied people who could be that way.

We walked three blocks to the Chayka restaurant. It was empty. The waiters were smoking at a side table. The windows were wide open. The curtains swayed in the breeze.

We decided to go to the far corner. A young man in a silvery Dacron[13] jacket stopped Fred. They had a rather mysterious conversation.

“Greetings.”

“My respects,” said Fred.

“Well?”

“Nothing.”

The young man’s eyebrows rose in disappointment. “Absolutely nothing?”

“Absolutely nothing.”

“But I asked you.”

“I’m very sorry.”

“But can I count on it?”

“Indubitably.”

“It would be good sometime this week.”

“I’ll try.”

“What about a guarantee?”

“No guarantees. But I’ll try.”

“Will it be a label?”

“Naturally.”

“So, call me.”

“Of course.”

“Do you remember my phone number?”

“Unfortunately I don’t.”

“Please write it down.”

“With pleasure.”

“Even though this is not a conversation for the phone.”

“I agree.”

“Maybe you’ll just come by with the wares?”

“Gladly.”

“Do you remember my address?”

“Afraid not…”

And so on.

We went to the far corner. The clear folds of the ironing showed on the tablecloth. The cloth was rough.

Fred said, “See that wannabe? A year ago he ordered a set of Delbanas with a cross-”

I interrupted him. “What are Delbanas with a cross?”

“Watches,” Fred replied. “It’s not important. I brought him the goods at least ten times. He wouldn’t take them. He came up with a new excuse each time. In the end, he never did take them. I kept thinking, ‘What’s he playing at?’ And suddenly I realized that he didn’t want to buy my watches, he just wanted to feel like a businessman who needed a shipment of brand-name goods. He wanted an excuse to keep asking me, ‘How is our arrangement?’”

The waitress took our order. We lit up our cigarettes and I asked, “Couldn’t you be arrested?”

Fred thought about it and replied calmly, “It’s not out of the question. I’ll be sold out by my own people,” he added without anger.

“Then maybe you should stop?”

He frowned. “I used to work as a shipping clerk[14].

I lived on ninety roubles a month…” Then he suddenly stood up and shouted, “It’s a farce!”

“Prison isn’t any better.”

“What can I do? I have no talents. I refuse to cripple myself for ninety roubles. Well, all right, so I’ll eat two thousand hamburgers in my lifetime. Wear out twenty-five dark-grey suits. Leaf through seven hundred issues of the local newspaper. And die without scratching the earth’s surface. Is that it?. I’d rather live only a minute, but live it right!”

Our food and drink was brought.

My new friend continued to philosophize. “There’s nothing before our birth but an abyss, and there’s only an abyss after our death. Our life is but a grain of sand in the indifferent ocean of infinity. So let’s try to keep the moment from boredom and despair! Let’s try to leave a scratch on the earth’s crust. Let the average Joe[15] pull the load. He’s not going to perform miracles. Or even commit crimes…”

I almost shouted at Fred, “Then why don’t you perform any miracles!” But I controlled myself. He was paying for the drinks.

We spent about an hour in the restaurant. Then I said, “Time to go. The pawnshop will close.”

And then Fred Kolesnikov made me an offer. “Want to get in on the share? I work carefully, I don’t take hard currency[16] or gold. You’ll improve your finances and then you can quit. How about it? Let’s have a drink now and talk tomorrow.”

The next day I thought my pal would stand me up, but Fred was merely late. We met near the idle fountain in front of the Astoria Hotel. Then we went off into the bushes. Fred said, “Two Finnish women will be here in a minute with the goods. Grab a cab and go with them to this address.”

He handed me a scrap of newsprint and went on. “Rymar will meet you. Easy to recognize – he’s got the face of an idiot and an orange sweater. I’ll be there after ten minutes. Everything will be OK!”

“But I don’t speak Finnish.”

“That doesn’t matter. The important thing is to smile. I’d go myself, but they know me here…” Fred suddenly grabbed my hand. “There they are! Go to it!”

And he disappeared into the bushes.

I went to meet the two women, feeling terribly nervous. They looked like peasants, with broad, tanned faces. They were wearing light raincoats, elegant shoes and bright kerchiefs. Each carried a shopping bag as swollen as a soccer ball.

Gesticulating wildly, I finally led the women to the taxi stand. There was no line. I kept repeating, “Mr Fred, Mr Fred,” and plucked at one woman’s sleeve.

“Where is that guy?” the woman said angrily. “Where the hell is he? What’s he trying to pull?[17] ”

“You speak Russian?”

“My mama was Russian.”

I said, “Mr Fred will be coming a bit later. Mr Fred asked me to take you to his house.”

A car pulled up. I gave the address. Then I started looking out the window. I hadn’t realized how many policemen there could be in a crowd of pedestrians.

The women spoke Finnish to each other. They were clearly unhappy about something. Then they laughed and I felt better.

A man in a fiery sweater was waiting for us on the sidewalk. He said to me with a wink, “What a couple of dogs!”

“Take a look in the mirror,” Ilona said angrily. She was the younger one.

“They speak Russian,” I said.

“Terrific,” Rymar said without skipping a beat, “marvellous. Brings us closer. How do you like Leningrad?”

“Not bad,” Maria said.

“Have you been to the Hermitage?”

“Not yet. What is it?”

“They have paintings, souvenirs, and so on. Before that, tsars lived in it,” said Rymar.

“We should take a look,” Ilona said.

“You haven’t been to the Hermitage!” Rymar was shocked. He even slowed his pace a bit, as if being with such uncultured people was dragging him down.

We went up to the second floor. Rymar pushed open the door, which wasn’t locked. There were dirty dishes everywhere. The walls were covered with photographs. Colourful dust jackets of foreign records lay on the couch. The bed wasn’t made.

Rymar put on the light and quickly neatened up. Then he said, “What have you brought?”

“Why don’t you tell us where your pal with the money is?”

There were footsteps at that moment, and Fred Kolesnikov appeared. He was carrying a newspaper that had been in his mailbox. He looked calm, even indifferent.

"Terse,” he said to the Finns. “Hello.”

Then he turned to Rymar. “Boy, they look pissed.

Have you been hitting on them?”

“Me?” said Rymar indignantly. “We were talking about Art! By the way, they speak Russian.”

“Wonderful,” said Fred. “Good evening, Madame Lenart; how are you, Mademoiselle Ilona?”

“All right, thanks.”

“Why did you hide the fact that you speak Russian?”

“No one asked.”

“We should have a drink first,” Rymar said.

He took a bottle of Cuban rum from the closet. The Finns drank with pleasure. Rymar poured another round. When the guests went to use the bathroom, he said, “All these Laplanders look alike.”

“Especially since they’re sisters,” Fred explained.

“Just as I thought… By the way, that mug of Mrs Lenart’s doesn’t inspire confidence in me.”

Fred yelled at Rymar, “And whose mug does inspire confidence in you, besides the mug of a police investigator?”

The Finns soon returned. Fred gave them a clean towel. They raised their glasses and smiled – the second time that day. They kept their shopping bags on their laps.

“Cheers!” Rymar said. “To victory over the Germans!”

We drank, and so did the Finns. A phonograph stood on the floor, and Fred turned it on with his foot. The black disc bobbed slightly.

“Who’s your favourite writer?” Rymar was bugging the Finns.

The women consulted each other. Then Ilona said, “Karjalainen, perhaps[18]?”

Rymar smiled condescendingly to indicate that he approved of the named candidate – but also that he himself had higher pretensions.

“I see,” he said. “What are your wares?”

“Socks,” Maria said.

“Nothing else?”

“What else would you like?”

“How much?” Fred inquired.

“Four hundred thirty-two roubles,” barked Ilona, the younger one.

“Mein Gott[19] !" Rymar exclaimed. “The bared fangs of capitalism!”

“I want to know how much you brought. How many pairs?” Fred demanded.

“Seven hundred and twenty.”

“Nylon crêpe?” Rymar demanded.

“Synthetic,” Ilona replied. “Sixty copecks the pair. Total, four hundred thirty-two roubles.”

Here I have to make a small mathematical digression. Crêpe socks were in fashion then. Soviet industry did not manufacture them, so you could buy them only on the black market. A pair of Finnish socks cost six roubles. The Finns were offering them for one tenth that amount. Nine hundred per cent pure profit…

Fred took out his wallet and counted out the money.

“Here,” he said, “an extra twenty roubles. Leave the goods right in the shopping bags.”

“We have to drink to the peaceful resolution of the Suez crisis[20]! To the annexation of Lotharingia!” said Rymar.

Ilona shifted the money to her left hand. She picked up her glass, which was filled to the brim.

“Let’s ball these Finns,” Rymar whispered, “in the name of international unity.”

Fred turned to me. “See what I have to work with?”

I felt anxious and scared. I wanted to leave as quickly as possible.

“Who’s your favourite artist?” Rymar asked Ilona. And he put his hand on her back.

“Maybe Mantere[21],” Ilona said, moving away.

Rymar lifted his brows in reproach, as if his aesthetic sense had been offended.

Fred said to me, “The women have to be seen off and the driver given seven roubles. I’d send Rymar, but he’ll filch part of the money.”

“Me?!” Rymar was incensed. “With my crystalclear honesty?”

When I got back, there were coloured cellophane packages everywhere. Rymar looked slightly crazed.

“Piastres, krona, dollars,” he mumbled, “francs…”

Suddenly he calmed down and took out a notebook and felt-tip pen[22]. He made some calculations and said, “Exactly seven hundred and twenty pairs. The Finns are an honest people. That’s what you get with an under-developed state.”

“Multiply by three,” Fred told him.

“Why by three?”

“The socks will go for three roubles if we sell them wholesale. Fifteen hundred plus of pure profit.”

Rymar immediately arrived at the precise figure. “One thousand seven hundred twenty-eight roubles.” Madness and practicality coexisted in him.

“Five hundred something for each of us,” Fred added.

“Five hundred seventy-six,” Rymar specified.

Later Fred and I were in a shashlik restaurant. The oilcloth on the table was sticky. The air was filled with a greasy fog. People floated past like fish in an aquarium. wFred looked distracted and gloomy. I said, “That much money in five minutes!”

I had to say something.

“You still have to wait forty minutes to get some greasy pies cooked in margarine,” Fred replied.

Then I asked, “What do you need me for?”

“I don’t trust Rymar. Not because Rymar might cheat a client, though that’s not out of the question. And not because Rymar can stick a client with old certificates instead of money. And not even because he tends to put his hands on the clients. But because Rymar is stupid. What destroys fools? A longing for Art and Beauty, and Rymar has this longing. Despite his historical limitations, he wants a Japanese portable radio. Rymar goes to the hard-currency store and hands the cashier forty dollars. With his face! Even in the most ordinary grocery store, when he hands the cashier a rouble, the cashier is sure the rouble’s stolen. And here he has forty dollars! A clear violation of the hard-currency regulations. Sooner or later he’ll wind up in jail.”

“What about me?”

“You won’t. You’ll have other problems.”

I didn’t ask which ones.

Taking his leave, Fred added, “You’ll get your share on Thursday.”

I went home feeling a strange mixture of anxiety and elation. There must be some vile power in crazy money.

I didn’t tell Asya about my adventure. I wanted to amaze her. To turn suddenly into a rich and expansive man.

Meanwhile, things were growing worse with her. I kept asking her questions. Even when I was putting down her friends, I used the interrogative form: “Don’t you think that Arik Shulman is a jerk?” I wanted to compromise Shulman in Asya’s eyes and achieved just the opposite, of course.

I’ll tell you, running ahead of my story, that we broke up in the fall. For sooner or later a person who keeps asking questions is going to learn to give answers…

Fred called on Thursday. “A catastrophe!”

I thought Rymar had been arrested.

“Worse,” said Fred. “Go into the nearest clothing store.”

“Why?”

“All the stores are flooded with crêpe socks. Soviet crêpe socks. Eighty copecks a pair. Quality no worse than the Finnish ones. The same synthetic shit.”

“What can we do?”

“Nothing. What could we do? Who would have expected a low blow like this from a socialist economy? Who can I give Finnish socks to now? They won’t take them for a rouble now! I know our damned industry. First they screw around[23] for twenty years and then – bam! And all the stores are filled with some crap or other. Once they get a production line going, that’s it. They’ll stamp out millions of those crêpe socks a minute.”

We divided up the socks. Each of us got two hundred forty pairs. Two hundred forty pairs of identical, ugly, pea-green-coloured socks. The only consolation was the “Made in Finland” label.

After that, many things happened. The operation with the Italian raincoats. The resale of six German stereos. A brawl in the Cosmos Hotel over a case of American cigarettes. Carrying a load of Japanese cameras and fleeing a police squad. And lots of other things.

I paid off my debts. Bought myself some decent clothes. Changed departments at college. Met the girl I eventually married. Went to the Baltics for a month when Rymar and Fred were arrested. Began my feeble literary attempts. Became a father. Got into trouble with the authorities. Lost my job. Spent a month in Kalyayevo Prison.

And only one thing did not change: for twenty years I paraded around in pea-coloured socks. I gave them to all my friends. Wrapped Christmas ornaments in them. Dusted with them. Stuck them into the cracks of window frames. And still the number of those lousy socks barely diminished.

And so I left, leaving a pile of Finnish crêpe socks in the empty apartment. I shoved three pairs in my suitcase.

They reminded me of my criminal youth, my first love and my old friends. Fred served his two years and then was killed in a motorcycle accident on his Chezet[24]. Rymar served one year and now works as a dispatcher in a meat-packing plant. Asya emigrated and teaches lexicology at Stanford – which is a strange comment on American scholarship.