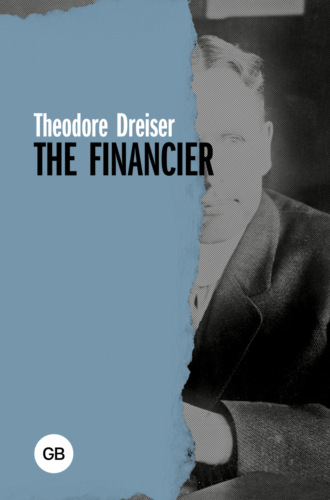

Теодор Драйзер

The Financier / Финансист

One of his earliest and most genuine leanings was toward paintings. He admired nature, but somehow, without knowing why, he fancied one could best grasp it through the personality of some interpreter, just as we gain our ideas of law and politics through individuals. Mrs. Cowperwood cared not a whit one way or another, but she accompanied him to exhibitions, thinking all the while that Frank was a little peculiar. He tried, because he loved her, to interest her in these things intelligently, but while she pretended slightly, she could not really see or care, and it was very plain that she could not.

The children took up a great deal of her time. However, Cowperwood was not troubled about this. It struck him as delightful and exceedingly worth while that she should be so devoted. At the same time, her lethargic manner, vague smile and her sometimes seeming indifference, which sprang largely from a sense of absolute security, attracted him also. She was so different from him! She took her second marriage quite as she had taken her first—a solemn fact which contained no possibility of mental alteration. As for himself, however, he was bustling about in a world which, financially at least, seemed all alteration—there were so many sudden and almost unheard-of changes. He began to look at her at times, with a speculative eye—not very critically, for he liked her—but with an attempt to weigh her personality. He had known her five years and more now. What did he know about her? The vigor of youth—those first years—had made up for so many things, but now that he had her safely…

There came in this period the slow approach, and finally the declaration, of war between the North and the South, attended with so much excitement that almost all current minds were notably colored by it. It was terrific. Then came meetings, public and stirring, and riots; the incident of John Brown’s body; the arrival of Lincoln, the great commoner, on his way from Springfield, Illinois, to Washington via Philadelphia, to take the oath of office; the battle of Bull Run; the battle of Vicksburg; the battle of Gettysburg, and so on. Cowperwood was only twenty-five at the time, a cool, determined youth, who thought the slave agitation might be well founded in human rights—no doubt was—but exceedingly dangerous to trade. He hoped the North would win; but it might go hard with him personally and other financiers. He did not care to fight. That seemed silly for the individual man to do. Others might—there were many poor, thin-minded, half-baked creatures who would put themselves up to be shot; but they were only fit to be commanded or shot down. As for him, his life was sacred to himself and his family and his personal interests. He recalled seeing, one day, in one of the quiet side streets, as the working-men were coming home from their work, a small enlisting squad of soldiers in blue marching enthusiastically along, the Union flag flying, the drummers drumming, the fifes blowing, the idea being, of course, to so impress the hitherto indifferent or wavering citizen, to exalt him to such a pitch, that he would lose his sense of proportion, of self-interest, and, forgetting all—wife, parents, home, and children—and seeing only the great need of the country, fall in behind and enlist. He saw one workingman swinging his pail, and evidently not contemplating any such denouement to his day’s work, pause, listen as the squad approached, hesitate as it drew close, and as it passed, with a peculiar look of uncertainty or wonder in his eyes, fall in behind and march solemnly away to the enlisting quarters. What was it that had caught this man, Frank asked himself. How was he overcome so easily? He had not intended to go. His face was streaked with the grease and dirt of his work—he looked like a foundry man or machinist, say twenty-five years of age. Frank watched the little squad disappear at the end of the street round the corner under the trees.

This current war-spirit was strange. The people seemed to him to want to hear nothing but the sound of the drum and fife, to see nothing but troops, of which there were thousands now passing through on their way to the front, carrying cold steel in the shape of guns at their shoulders, to hear of war and the rumors of war. It was a thrilling sentiment, no doubt, great but unprofitable. It meant self-sacrifice, and he could not see that. If he went he might be shot, and what would his noble emotion amount to then? He would rather make money, regulate current political, social and financial affairs. The poor fool who fell in behind the enlisting squad—no, not fool, he would not call him that—the poor overwrought working-man—well, Heaven pity him! Heaven pity all of them! They really did not know what they were doing.

One day he saw Lincoln—a tall, shambling man, long, bony, gawky, but tremendously impressive. It was a raw, slushy morning of a late February day, and the great war President was just through with his solemn pronunciamento in regard to the bonds that might have been strained but must not be broken. As he issued from the doorway of Independence Hall, that famous birthplace of liberty, his face was set in a sad, meditative calm. Cowperwood looked at him fixedly as he issued from the doorway surrounded by chiefs of staff, local dignitaries, detectives, and the curious, sympathetic faces of the public. As he studied the strangely rough-hewn countenance a sense of the great worth and dignity of the man came over him.

“A real man, that,” he thought; “a wonderful temperament.” His every gesture came upon him with great force. He watched him enter his carriage, thinking “So that is the railsplitter, the country lawyer. Well, fate has picked a great man for this crisis.”

For days the face of Lincoln haunted him, and very often during the war his mind reverted to that singular figure. It seemed to him unquestionable that fortuitously he had been permitted to look upon one of the world’s really great men. War and statesmanship were not for him; but he knew how important those things were—at times.

Chapter XI

It was while the war was on, and after it was perfectly plain that it was not to be of a few days’ duration, that Cowperwood’s first great financial opportunity came to him. There was a strong demand for money at the time on the part of the nation, the State, and the city. In July, 1861, Congress had authorized a loan of fifty million dollars, to be secured by twenty-year bonds with interest not to exceed seven per cent., and the State authorized a loan of three millions on much the same security, the first being handled by financiers of Boston, New York, and Philadelphia, the second by Philadelphia financiers alone. Cowperwood had no hand in this. He was not big enough. He read in the papers of gatherings of men whom he knew personally or by reputation, “to consider the best way to aid the nation or the State”; but he was not included. And yet his soul yearned to be of them. He noticed how often a rich man’s word sufficed—no money, no certificates, no collateral, no anything—just his word. If Drexel & Co., or Jay Cooke & Co., or Gould & Fiske were rumored to be behind anything, how secure it was! Jay Cooke, a young man in Philadelphia, had made a great strike taking this State loan in company with Drexel & Co., and selling it at par. The general opinion was that it ought to be and could only be sold at ninety. Cooke did not believe this. He believed that State pride and State patriotism would warrant offering the loan to small banks and private citizens, and that they would subscribe it fully and more. Events justified Cooke magnificently, and his public reputation was assured. Cowperwood wished he could make some such strike; but he was too practical to worry over anything save the facts and conditions that were before him.

His chance came about six months later, when it was found that the State would have to have much more money. Its quota of troops would have to be equipped and paid. There were measures of defense to be taken, the treasury to be replenished. A call for a loan of twenty-three million dollars was finally authorized by the legislature and issued. There was great talk in the street as to who was to handle it—Drexel & Co. and Jay Cooke & Co., of course.

Cowperwood pondered over this. If he could handle a fraction of this great loan now—he could not possibly handle the whole of it, for he had not the necessary connections—he could add considerably to his reputation as a broker while making a tidy sum. How much could he handle? That was the question. Who would take portions of it? His father’s bank? Probably. Waterman & Co.? A little. Judge Kitchen? A small fraction. The Mills-David Company? Yes. He thought of different individuals and concerns who, for one reason and another—personal friendship, good-nature, gratitude for past favors, and so on—would take a percentage of the seven-percent. bonds through him. He totaled up his possibilities, and discovered that in all likelihood, with a little preliminary missionary work, he could dispose of one million dollars if personal influence, through local political figures, could bring this much of the loan his way.

One man in particular had grown strong in his estimation as having some subtle political connection not visible on the surface, and this was Edward Malia Butler. Butler was a contractor, undertaking the construction of sewers, water-mains, foundations for buildings, street-paving, and the like. In the early days, long before Cowperwood had known him, he had been a garbage-contractor on his own account. The city at that time had no extended street-cleaning service, particularly in its outlying sections and some of the older, poorer regions. Edward Butler, then a poor young Irishman, had begun by collecting and hauling away the garbage free of charge, and feeding it to his pigs and cattle. Later he discovered that some people were willing to pay a small charge for this service. Then a local political character, a councilman friend of his—they were both Catholics—saw a new point in the whole thing. Butler could be made official garbage-collector. The council could vote an annual appropriation for this service. Butler could employ more wagons than he did now—dozens of them, scores. Not only that, but no other garbage-collector would be allowed. There were others, but the official contract awarded him would also, officially, be the end of the life of any and every disturbing rival. A certain amount of the profitable proceeds would have to be set aside to assuage the feelings of those who were not contractors. Funds would have to be loaned at election time to certain individuals and organizations—but no matter. The amount would be small. So Butler and Patrick Gavin Comiskey, the councilman (the latter silently) entered into business relations. Butler gave up driving a wagon himself. He hired a young man, a smart Irish boy of his neighborhood, Jimmy Sheehan, to be his assistant, superintendent, stableman, bookkeeper, and what not. Since he soon began to make between four and five thousand a year, where before he made two thousand, he moved into a brick house in an outlying section of the south side, and sent his children to school. Mrs. Butler gave up making soap and feeding pigs. And since then times had been exceedingly good with Edward Butler.

He could neither read nor write at first; but now he knew how, of course. He had learned from association with Mr. Comiskey that there were other forms of contracting—sewers, water-mains, gas-mains, street-paving, and the like. Who better than Edward Butler to do it? He knew the councilmen, many of them. Het met them in the back rooms of saloons, on Sundays and Saturdays at political picnics, at election councils and conferences, for as a beneficiary of the city’s largess he was expected to contribute not only money, but advice. Curiously he had developed a strange political wisdom. He knew a successful man or a coming man when he saw one. So many of his bookkeepers, superintendents, time-keepers had graduated into councilmen and state legislators. His nominees—suggested to political conferences—were so often known to make good. First he came to have influence in his councilman’s ward, then in his legislative district, then in the city councils of his party—Whig, of course—and then he was supposed to have an organization.

Mysterious forces worked for him in council. He was awarded significant contracts, and he always bid. The garbage business was now a thing of the past. His eldest boy, Owen, was a member of the State legislature and a partner in his business affairs. His second son, Callum, was a clerk in the city water department and an assistant to his father also. Aileen, his eldest daughter, fifteen years of age, was still in St. Agatha’s, a convent school in Germantown. Norah, his second daughter and youngest child, thirteen years old, was in attendance at a local private school conducted by a Catholic sisterhood. The Butler family had moved away from South Philadelphia into Girard Avenue, near the twelve hundreds, where a new and rather interesting social life was beginning. They were not of it, but Edward Butler, contractor, now fifty-five years of age, worth, say, five hundred thousand dollars, had many political and financial friends. No longer a “rough neck,” but a solid, reddish-faced man, slightly tanned, with broad shoulders and a solid chest, gray eyes, gray hair, a typically Irish face made wise and calm and undecipherable by much experience. His big hands and feet indicated a day when he had not worn the best English cloth suits and tanned leather, but his presence was not in any way offensive—rather the other way about. Though still possessed of a brogue, he was soft-spoken, winning, and persuasive.

He had been one of the first to become interested in the development of the street-car system and had come to the conclusion, as had Cowperwood and many others, that it was going to be a great thing. The money returns on the stocks or shares he had been induced to buy had been ample evidence of that, He had dealt through one broker and another, having failed to get in on the original corporate organizations. He wanted to pick up such stock as he could in one organization and another, for he believed they all had a future, and most of all he wanted to get control of a line or two. In connection with this idea he was looking for some reliable young man, honest and capable, who would work under his direction and do what he said. Then he learned of Cowperwood, and one day sent for him and asked him to call at his house.

Cowperwood responded quickly, for he knew of Butler, his rise, his connections, his force. He called at the house as directed, one cold, crisp February morning. He remembered the appearance of the street afterward—broad, brick-paved sidewalks, macadamized roadway, powdered over with a light snow and set with young, leafless, scrubby trees and lamp-posts. Butler’s house was not new—he had bought and repaired it—but it was not an unsatisfactory specimen of the architecture of the time. It was fifty feet wide, four stories tall, of graystone and with four wide, white stone steps leading up to the door. The window arches, framed in white, had U-shaped keystones. There were curtains of lace and a glimpse of red plush through the windows, which gleamed warm against the cold and snow outside. A trim Irish maid came to the door and he gave her his card and was invited into the house.

“Is Mr. Butler home?”

“I’m not sure, sir. I’ll find out. He may have gone out.”

In a little while he was asked to come upstairs, where he found Butler in a somewhat commercial-looking room. It had a desk, an office chair, some leather furnishings, and a bookcase, but no completeness or symmetry as either an office or a living room. There were several pictures on the wall—an impossible oil painting, for one thing, dark and gloomy; a canal and barge scene in pink and nile green for another; some daguerreotypes of relatives and friends which were not half bad. Cowperwood noticed one of two girls, one with reddish-gold hair, another with what appeared to be silky brown. The beautiful silver effect of the daguerreotype had been tinted. They were pretty girls, healthy, smiling, Celtic, their heads close together, their eyes looking straight out at you. He admired them casually, and fancied they must be Butler’s daughters.

“Mr. Cowperwood?” inquired Butler, uttering the name fully with a peculiar accent on the vowels. (He was a slow-moving man, solemn and deliberate.) Cowperwood noticed that his body was hale and strong like seasoned hickory, tanned by wind and rain. The flesh of his cheeks was pulled taut and there was nothing soft or flabby about him.

“I’m that man.”

“I have a little matter of stocks to talk over with you” (“matter” almost sounded like “mather”), “and I thought you’d better come here rather than that I should come down to your office. We can be more private-like, and, besides, I’m not as young as I used to be.”

He allowed a semi-twinkle to rest in his eye as he looked his visitor over.

Cowperwood smiled.

“Well, I hope I can be of service to you,” he said, genially.

“I happen to be interested just at present in pickin’ up certain street-railway stocks on ’change. I’ll tell you about them later. Won’t you have somethin’ to drink? It’s a cold morning.”

“No, thanks; I never drink.”

“Never? That’s a hard word when it comes to whisky. Well, no matter. It’s a good rule. My boys don’t touch anything, and I’m glad of it. As I say, I’m interested in pickin’ up a few stocks on ’change; but, to tell you the truth, I’m more interested in findin’ some clever young felly like yourself through whom I can work. One thing leads to another, you know, in this world.” And he looked at his visitor non-committally, and yet with a genial show of interest.

“Quite so,” replied Cowperwood, with a friendly gleam in return.

“Well,” Butler meditated, half to himself, half to Cowperwood, “there are a number of things that a bright young man could do for me in the street if he were so minded. I have two bright boys of my own, but I don’t want them to become stock-gamblers, and I don’t know that they would or could if I wanted them to. But this isn’t a matter of stock-gambling. I’m pretty busy as it is, and, as I said awhile ago, I’m getting along. I’m not as light on my toes as I once was. But if I had the right sort of a young man—I’ve been looking into your record, by the way, never fear—he might handle a number of little things—investments and loans—which might bring us each a little somethin’. Sometimes the young men around town ask advice of me in one way and another—they have a little somethin’ to invest, and so—”

He paused and looked tantalizingly out of the window, knowing full well Cowperwood was greatly interested, and that this talk of political influence and connections could only whet his appetite. Butler wanted him to see clearly that fidelity was the point in this case—fidelity, tact, subtlety, and concealment.

“Well, if you have been looking into my record,” observed Cowperwood, with his own elusive smile, leaving the thought suspended.

Butler felt the force of the temperament and the argument. He liked the young man’s poise and balance. A number of people had spoken of Cowperwood to him. (It was now Cowperwood & Co. The company was fiction purely.) He asked him something about the street; how the market was running; what he knew about street-railways. Finally he outlined his plan of buying all he could of the stock of two given lines—the Ninth and Tenth and the Fifteenth and Sixteenth—without attracting any attention, if possible. It was to be done slowly, part on ’change, part from individual holders. He did not tell him that there was a certain amount of legislative pressure he hoped to bring to bear to get him franchises for extensions in the regions beyond where the lines now ended, in order that when the time came for them to extend their facilities they would have to see him or his sons, who might be large minority stockholders in these very concerns. It was a far-sighted plan, and meant that the lines would eventually drop into his or his sons’ basket.

“I’ll be delighted to work with you, Mr. Butler, in any way that you may suggest,” observed Cowperwood. “I can’t say that I have so much of a business as yet—merely prospects. But my connections are good. I am now a member of the New York and Philadelphia exchanges. Those who have dealt with me seem to like the results I get.”

“I know a little something about your work already,” reiterated Butler, wisely.

“Very well, then; whenever you have a commission you can call at my office, or write, or I will call here. I will give you my secret operating code, so that anything you say will be strictly confidential.”

“Well, we’ll not say anything more now. In a few days I’ll have somethin’ for you. When I do, you can draw on my bank for what you need, up to a certain amount.” He got up and looked out into the street, and Cowperwood also arose.

“It’s a fine day now, isn’t it?”

“It surely is.”

“Well, we’ll get to know each other better, I’m sure.”

He held out his hand.

“I hope so.”

Cowperwood went out, Butler accompanying him to the door. As he did so a young girl bounded in from the street, red-cheeked, blue-eyed, wearing a scarlet cape with the peaked hood thrown over her red-gold hair.

“Oh, daddy, I almost knocked you down.”

She gave her father, and incidentally Cowperwood, a gleaming, radiant, inclusive smile. Her teeth were bright and small, and her lips bud-red.

“You’re home early. I thought you were going to stay all day?”

“I was, but I changed my mind.”

She passed on in, swinging her arms.

“Yes, well—” Butler continued, when she had gone. “Then well leave it for a day or two. Good day.”

“Good day.”

Cowperwood, warm with this enhancing of his financial prospects, went down the steps; but incidentally he spared a passing thought for the gay spirit of youth that had manifested itself in this red-cheeked maiden. What a bright, healthy, bounding girl! Her voice had the subtle, vigorous ring of fifteen or sixteen. She was all vitality. What a fine catch for some young fellow some day, and her father would make him rich, no doubt, or help to.