Юрий Сорока

100 Key Ukrainian Personalities

© Yu. Soroka, 2019

© G. Krapivnyk, L. Gerasymchuk, translation, 2019

© О. Huhalova-Mieshkova, graphic design, 2019

© Publishing House «Folio», series, 2018

Askold and Dir (IX century)

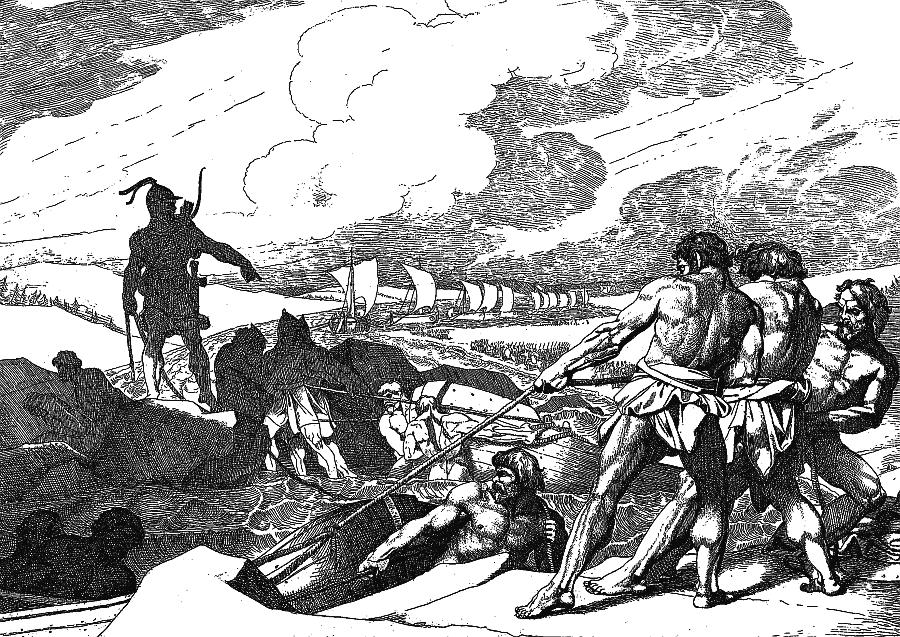

The period of Princes Askold and Dir rule over Kyivan Rus’ has been researched so insufficiently that it is impossible to confirm or deny any data about their lives registered by the chronicles. In fact, there are several versions as to the origin of the ancient Princes. According to the academic historiography, Askold and Dir reigned over Kyiv in the 860-880s. In 866 The Tale of Bygone Years informed, “…Askold and Dir went on a campaign to the Greeks and surrounded Tsargorod with 200 ships…” According to the chronicle, Emperor Michael had to pay the indemnity and sign a peace treaty favouring the Rusiches.

Askold and Dir (Radziwiłł, or Königsberg Chronicle)

However, if the chronicle confirms the existence of Askold and Dir, it does not specify who those people were. As to Askold, Nestor’s chronicle calls him one of Rurik’s governors (called voyevodas). On the contrary, the Kyivan Chronicle of approximately 1037–1039 runs that Askold and Dir were brothers and legendary Kyi’s descendants. Later researchers, though, question the authenticity of this part of the Kyivan chronicle. They claim that at first the chronicle mentioned Askold only. Dir’s name was added later. The fact that Askold and Dir ruled Kyiv is disproved by the details of their burial. According to the chronicle, Oleh’s soldiers killed both Princes at the same time. Then a question arises, “Why were they buried in different parts of Kyiv at a distance from one another?” Nestor mentions the fact, “And Dir’s tomb is behind Saint Oryna”.

The fact that Askold and Dir reigned at different time is fixed in the work of Al-Masudi, Arab geographer of the tenth century. He claimed that “Dir was the first Slavic tsar”. Following his works, historians believe that Dir ruled after Askold, mainly in the 870-880s. In that case, on entering Kyiv, Oleh’s soldiers killed just Dir while Askold had died earlier.

The Death of Askold and Dir. Print by F. Bruni, 1839

As to the coverage of the early years of the Kyivan Rus’, it is worth mentioning a study by Omelian Pritsak, a Ukrainian historian, who had to immigrate to the USA in 1943. Some parts of the scholar’s research support academic historians’ conclusions about the lives of Askold and Dir. However, the books indicate some interesting differences. In the scholar’s opinion, in 860, the campaign to Byzantium was organized by two Viking military leaders under the names Hasting and Bjorn. It was they who headed the troops and led them from Tmutarakan through the Sea of Azov to Constantinople. After the Byzantines agreed to pay a ransom, Hasting and Bjorn retreated. According to some Scandinavian sources referred to by Omelian Pritsak, Hasting went to Britain while Bjorn stayed in Polotsk to reign. It was in Polotsk that he was killed by a Viking named Lot Knaut, also known as Helg, or Oleh the Prophet. It is not hard to guess that Hasting and Bjorn were actually Askold and Dir. It is up to the reader to decide which version about the Princes’ lives is true. However, the fact that each of them contributed a lot to the Kyivan state history is undoubted.

Silver coin Askold, issued by the NBU

Rurik (?-879)

Prince Rurik is one of those images in the Ukrainian history that are most controversial, and few reliable sources are available to help and find the historical truth. Since time immemorial, scholars broke too many lances, published thousands of books and completed a huge number of historical studies of Rurik. Since the medieval times, his image has been used for fictional and scientific purposes as well as imperial propaganda, and due to all that the image is now buried under numerous pseudo-historical details. Without joining the dispute on their truthfulness, we may consider what Nestor the Chronicler wrote about Rurik in The Tale of Bygone Years.

Rurik. From the Title reference book. 1672

Explaining the origin of Kyivan Princes’ dynasty, Nestor referred to the tale about the three brothers’ arrival from the Norman lands. The Slavs decided to take the state power in Rus’ over.

“…From Germans the three brothers came with their relatives and a lot of soldiers. Rurik came to the throne in Novgorod, his brother Syneus – near the White Lake, and Truvor – in Izborsk. And they started to fight everywhere. From those settled Vikings the name Rus’ originated. After those Vikings the land of Rus’ got named”.

The brothers’ names mentioned by Nestor correspond to Scandinavian Hrorekr, Signiutr and Torvarr. It was this fact that supported the version about Norman origin of Rurik dynasty. As the chronicle reports, two years after the Vikings settled in Rus’, brothers Syneus and Truvor died and the power was concentrated in Rurik’s hands. However, some historians believe that Rurik’s brothers did not exist in fact and their names can be interpreted as merely inadequate translation of the Swedish words ‘his clan’ (sine hus) and ‘faithful wife’ (thru varing).

“And he came to the throne there and distributed districts to his men ordering them to found towns: one of them – Polotsk, some other – Rostov, one more – Biloozero (the White Lake). But the Vikings were the newcomers there. The first settlers in Novgorod were the Slovens, in Polotsk – the Kryvyches, in Rostov – the Merya, in Biloozero – the Ves’, and in Murom – the Muroms. And Rurik ruled over them all”.

The chronicles do not tell about Prince Rurik’s further life. It is known that in 864 Novgorod inhabitants rebelled against Rurik’s rule. As a result, the prince had to take very cruel measures to keep his power. As the Nykon chronicle of the first half of the XVII century goes, by Rurik’s order, Vadym the Brave, a representative of Novgorod nobility was killed, and “a lot of other people from Novgorod, his advisers” were killed, too.

It should be noted that Prince Rurik is often mistaken for Danish konung Rurik from Jutland who was in service with Carolingian Dynasty and lived approximately at the same time to which The Tale of Bygone Years indicates, telling about the founder of the ruling dynasty in Kyivan Rus’. However, contemporary historiography cannot prove or disprove the theory due to lack of sources. Pursuant to the chronicle data, Prince Rurik died in 879. He left his son Ihor who later came to Kyiv throne.

V. Vasnetsov. Rurik’s arrival in Ladoga

Oleh the Prophet (? – 912 (922))

The birth date of Konung Helg, traditionally called Oleh the Prophet by the Slavs, is not known exactly. Still, contrary to Kyi, Shcheck, Khoriv as well as Askold and Dir, we know a lot about Oleh’s life. He came to Rus’ in Rurik’s troops and, as some sources say, was a relative of him. After Rurik’s death, having been appointed the regent to young Prince Ihor, Oleh usurped the power in Novgorod and then campaigned south and conquered Kyiv. It was there that Oleh decided to place a mighty state capital. The Tale of Bygone Years proclaims the year of 882 as the date when Oleh came to the throne -

“And there went Oleh taking a lot of his soldiers with him. The Vikings, Chud’, Slovens, Merya, Ves’, and Kryvyches. And he came up to Smolensk with his Kryvyches. And he captured the town of Smolensk. And he made a man of his reign there. And he went down form there. And he captured Lyubech making a man of his reign there. And he came up to the Kyivan Mountains…”

Kyiv Prince Oleh (or Oleg of Novgorod) (Radziwiłł Chronicle)

From then on, as the chronicle runs that Oleh decided to settle in Kyiv. In its turn, Novgorod had to pay 300 hryvnias as an annual tribute. It is to be noted that Novgorod inhabitants continued to pay the tribute to Kyiv till the days of Yaroslav the Wise’s reign.

When Oleh, who appeared to be a most wise political leader, came to power, Kyivan Rus’ was quickly gaining the weight in Middle Age Europe. The borders of Rus’ stretched from the Baltic Sea to the Dnieper. Gradually, by taking political measures and military actions, Oleh conquered the tribe unions of the Drevlians, Radymyches, and Siverians that gave him a mighty resource for further conquests. Then the Khazar Khaganate that was a constant threat to Kyiv was defeated. At that stage, the prince, following some of his predecessors, started thinking about conquering the coast of rich Byzantium. The Novgorod chronicle and The Tale of Bygone Years report that the Rusiches went to Tsargorod in 907. Having gathered numerous troops, Oleh surrounded the city and made the Byzantines sign a peace treaty, the final version of which appeared in 911. However, in fairness, we note that the campaign in question was mentioned in Rus’ chronicles only, and left no traces in Byzantine ones.

Oleh’s Campaign to Constantinople. Print by F. Bruni, 1839

The circumstances of Oleh the Prophet death are not clear. Nestor Chornoryasnyk (Black Cassock) supplies a romantic tale about the prince’s death after a bite of a snake that appeared from the skull of his favourite horse. Contrary to that, the Novgorod chronicle, without any details, informs that Oleh died “overseas”. The chronicles also differed as to the date of the prince’s death. The Tale of Bygone Years mentions 912. Instead, the Novgorod chronicle indicates 922. Arab geographer, Al’-Masudi’s works threw more light on the circumstances of Prince Oleh’s death. The geographer informs that in 912 or 913 the Rusiches headed by Oleh the Prophet sailed up the Don in 500 boats, dragged the boats to the Volga and went on a campaign over the Caspian Sea. According to Al’-Masudi’s evidence, the Rusiches were defeated during the campaign and nearly all of them perished. Prince Oleh might have been among the killed.

Ihor Rurikovych (878–945)

Ihor is known as the first Kyivan prince of Rurik’s dynasty. Having appeared in Kyiv in the company of Oleh the Prophet, Ihor began to reign only after Oleh’s death, that is, in 912 or 913. The Tale of Bygone Years informs us-

“In the year of 6421 (913) Ihor started to reign after Oleh. At the same time Constantine, Leo’s son and Roman’s son-in-law, began to reign in Tsargorod. The Drevlians unleashed the war against Ihor after Oleh’s death”.

Ihor levies duty from the Drevlians (Radziwiłł Chronicle)

It should be noted that Ihor’s reign succeeded and followed Oleh the Prophet’s development of Kyivan Rus’. Just before his death, Oleh managed to marry his ward. Some historians believe that his marriage to Olha took place in 903. But there are no proves to that and the version causes some doubt, if only because of the fact that Sviatoslav, a son of Ihor by Olha, was born in 942. Ihor was baptized by fire in 914 during the military campaign against the tribes of the Drevlians. Though the Drevlians had been conquered by Ihor’s predecessor, they persistently did not recognize the supremacy of Kyivan princes. The campaign against Iskorosten, the Drevlians’ capital, turned to be a success for Ihor. He won a victory and, as a result, the tribute of the Drevlians set by Oleh was considerably increased. The next year, in 915, Kyiv troops headed by Ihor started fighting against the Pechenegs. Owing to a successful campaign against those nomads, a peace treaty was signed and for the next five years, Kyivan lands were safe from the Pechenegs’ attacks. Eastern historical sources mention Ihor’s campaigns as well. For instance, in his works, Nisami Gyangevi, a Persian poet, scholar and thinker, described looting and destruction of the city of Berdaa, situated in today’s Azerbaijan, by the Rusiches headed by Ihor.

As to the relations with the Byzantine Empire, Ihor, Rurik’s son, led the policy traditional for his predecessors. It is known that in 941 he went on a military campaign against Tsargorod. But the military fortune turned away from the prince – his fleet was burnt down with the fire of the Greeks and his troops were defeated. The Tale of Bygone Years describes the event in the following way-

“…But Theophanes met them with fire from his ships. He began sent fire by pipes to the Rus’ ships. It was an awful sight. The Rus’ fighters saw the flame and began to dive into the sea water…”

In spite of the defeat, prince Ihor organized a still larger scale campaign against Tsargorod and finally achieved his goal. As a result, after the Rusiches’ victory, a peace treaty beneficial for Kyiv was concluded.

Ihor died in 945 being killed by the Drevlians. It is believed that his death resulted from the ill-conceived policy of taxing. Though Iskorosten paid everything according to the previous agreement, Prince Ihor tried to tax his vassals once again. It provoked a rebellion of the Drevlians headed by Prince Mal. They defeated Ihor’s detachment, captured Prince Ihor a prisoner and, as Leo Deacon, a chronicler, tells, executed him by tying to trees.

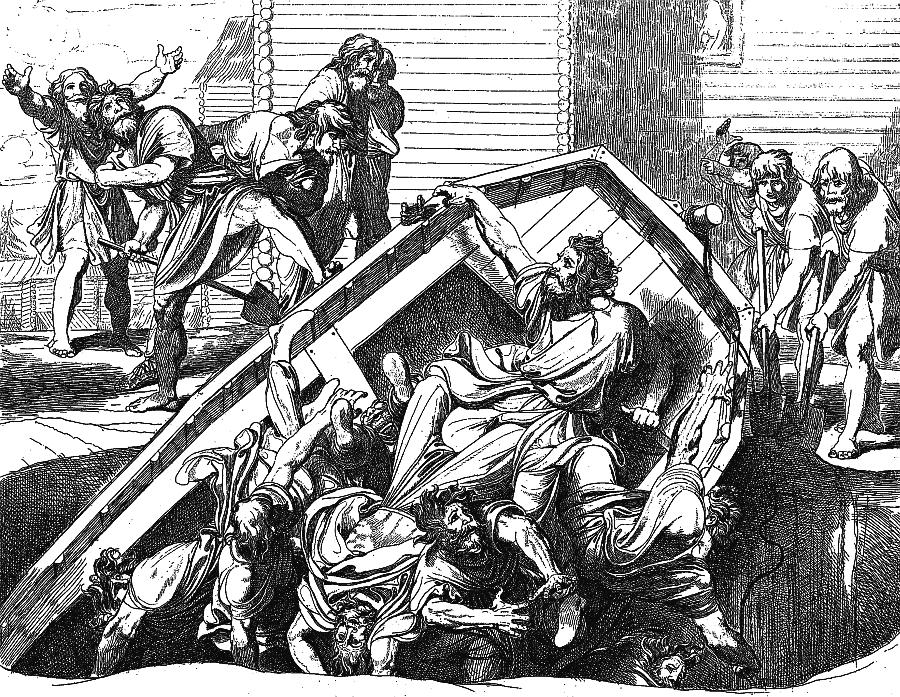

Prince Ihor’s Execution. Illustration by F. Bruni

Princess Olha (?-969)

Princess Olha’s, Ihor’s wife, date of birth and origin are unknown. Historians’ suggestions can be divided into four groups. Olha’s origin is ascribed to Pskov, Kyiv, Galych and Bulgaria. The Tale of Bygone Years by Nestor Chornoryasnyk runs as follows-

“…Ihor grew up and went to levy tributes after Oleh. People listened to him and brought him a wife from Pleskov, Olha by name”.

We understand that chronicles provide only approximate data on Olha’s life. Some historians view 910 as the year of her birth. In that case, Olha married Ihor about 930. It was proved by the chronicles that mention Olha was not the only wife of Prince Ihor, that fact might have caused Nestor the Chronicler’s mistake.

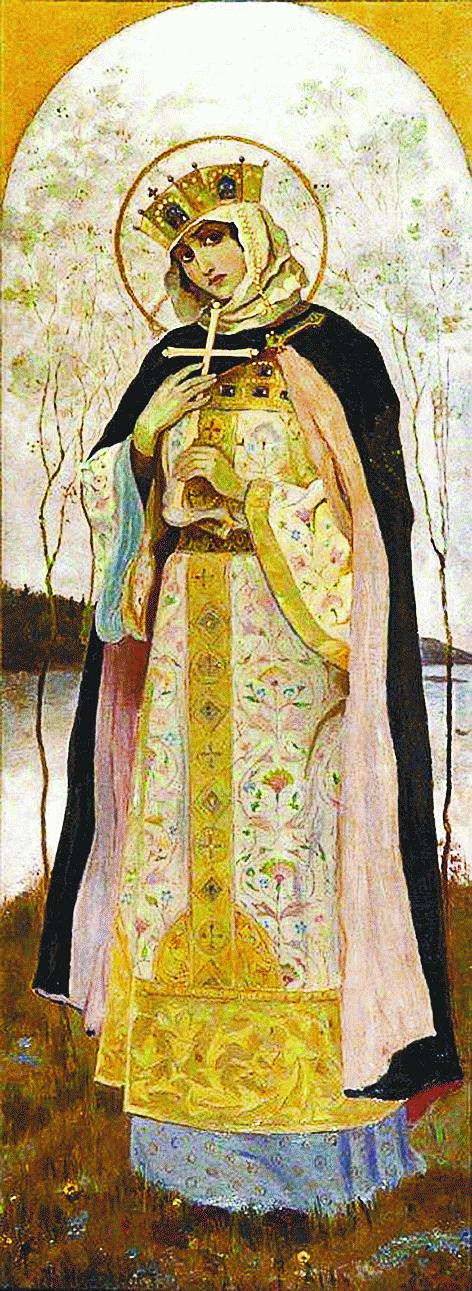

М. Nesterov. Saint Princess Olha. A design from the Kyiv Volodymyr Cathedral

Olha’s real talent as a political leader manifested itself after Ihor’s death. Taking the responsibility of ruling Kyivan Rus’ till Sviatoslav, her son, came of age, Olha proved that she could lead domestic and foreign policy of the princedom no worse than men. One of the first actions of hers, recorded in the chronicles, was the act of revenge on the Drevlians for her husband’s murder. Viewing Olha as a weak opponent, Mal, Drevlian Prince, sent an embassy to Kyiv and proposed to Olha, thus trying to unite Iskorosten and Kyiv.

“And the Drevlians tell her, “We have been sent by the Drevlian land to tell you this: your husband was killed since he stole from us and robbed us as a wolf. And our princes are kind as they have made our land rich. So marry our prince, our Mal”.

However, the proposal was fatal both for Mal himself and his embassy. Olha ordered to kill ambassadors and then set off to the Drevlian lands and burnt Iskorosten’ down.

“And Olha ordered her soldiers to catch them. And when she took the town, she burnt it down. And she burnt down the elders, killing other people as well”.

Later, Olha continued Kyivan princes’ foreign policy whose foundations were laid by Askold and Dir. First of all, it was, strengthening the relations with the Byzantine Empire. It is known that in 946 and in 957 Olha visited Tsargorod and the chronicles inform us about the visits in detail. Two pacts were signed between the allies then according to which Kyivan warriors were to serve the Emperor and Byzantium was to pay a tribute to Rus’ for that. During one of the visits to Tsargorod, Princess Olha was solemnly baptized. She was baptized by the Orthodox patriarch. The ritual was held in the Sophia Cathedral, the main cathedral in the Empire. Historians believe that the next Olha’s step might have been the introduction of Cristianity in Rus’ but due to unknown reasons, it did not happen.

As chronicles say, Olha transferred the reign to her son, Sviatoslav, in 964. Some researchers think that it was done under the pressure of Sviatoslav himself who was considered an ardent Pagan. That version also accounts for Olha’s unsuccessful attempt to introduce Christianity in Rus’. Olha died in 969 in Kyiv and the church chronicle registered that.

Olha’s Revenge on Drevlians’ idols. Print by F. Bruni

Sviatoslav (931 (938) – 972)

Historians have been depicting Sviatoslav Ihorovych as a hero-conqueror and an ascetic warrior. Although there is some logic there, it should be noted that foreign military campaigns did not prevent Sviatoslav from caring about his native country.

The Tale of Bygone Years presents a lively romantic portrait of Sviatoslav-

“When Prince Sviatoslav grew up and matured, he started gathering a lot of brave warriors. And he himself was brave and with easy gait like a leopard. And he fought a lot of wars. And he took neither any carts with him, nor pots, and did not boil any meat. He thinly cut some horsemeat, or game, or veal and broiled it and ate. And he had no tent but laid down in a numdah and put a saddle under his head. And all his warriors did the same. And he sent them to other lands saying, “I want to fight against you”.

Sviatoslav. Probably, portrait of Sviatoslav Ihorovych from the Title reference book. XVII century

Since the very beginning of Sviatoslav’s reign, Kyivan Rus’ declared to its enemies nearby that it was ruled by a warrior who did not only preserve what had been gained by his predecessors but also essentially expanded and strengthened all the gains. During his two victorious campaigns of 965 and 968, Sviatoslav practically destroyed the Khazar Khaganate that had been a constant threat to Kyiv. Similar successful was observed in Sviatoslav’s campaign against Byzantium and Bulgaria, its vassal, in 968–971. In 971, surrounded in Dorostol, a Bulgarian town, Sviatoslav showed his talent as a capable politician by signing a peace treaty with Emperor John Tzimiskes, which was rather beneficial for Kyiv. According to the peace treaty, the Rusiches were granted the right to leave the town armed and get some food for their return home.

Sviatoslav. Prince’s emblem

Historians of different periods portrayed Sviatoslav in detail, ascribing the traits of a real warrior and politician to him. One of the best known is the descriptions of Sviatoslav’s appearance by Leo Deacon, a Byzantine chronicler of the tenth century-

“There appeared Sviatoslav who sailed by the river on a Scythian boat. He was sitting and rowing together with his warriors just like one of them. His appearance was like this: he was neither tall, nor short, with bushy eyebrows and blue eyes, he was snub-nosed and clearly-shaven. He had long moustache above his upper lip. His head was shaven but on the one side there was hanging a strand of hair – a sign of noble origin. His neck was thick, his chest was broad and other parts of his body were quite presentable but he looked gloomy and wild. In one ear he was wearing a golden earring with a diamond and two pearls. His clothes were white and differed from the clothes of his warriors only by their cleanness. Sitting in the boat, he spoke with the emperor about state affairs and left”.

Taking that evidence into consideration, one cannot but draw a parallel between the Prince’s appearance and that of his descendants – Ukrainian Cossacks. M. Hrushevsky referred to Sviatoslav as “the first Zaporizhzhian on the Kyivan throne” or “a Spartan of Ancient Rus’”.

In March, 972, Sviatoslav perished in the battle against the Pechenegs on the island of Khortitsa. It is known that Kurya, the Pecheneg Khan made a wine cup from his skull. For us, Sviatoslav remains a model of courage, honesty, and stamina of a great military leader of Rus’.

І. Akimov. Great Prince Sviatoslav kisses his mother and children on returning from the Danube to Kyiv