Гилберт Кит Честертон

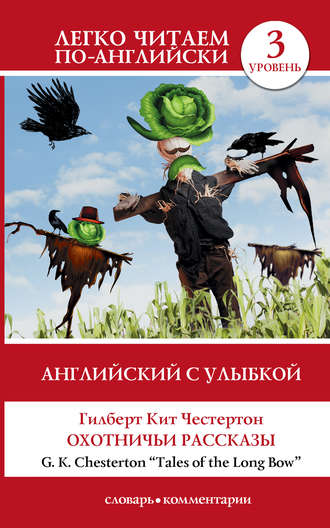

Английский с улыбкой. Охотничьи рассказы / Tales of the Long Bow

“Good morning, Colonel,” said the doctor more loudly than usual, “what a f… what a fine day it is.”

Stars turned from their courses like comets, so to speak, and the world moved towards wilder variants, at that crucial moment when Dr. Hunter corrected himself and said, “What a fine day!” instead of “What a funny hat!” The reason why he corrected himself, a true picture of what passed through his mind might sound rather exotic in itself. It would be less than enough to say he did so because of a long grey car waiting outside the Colonel’s house. It might not be a complete explanation to say it was because of a lady walking on stilts at a garden party. It might still not be clear, even if we said that it had something to do with a nickname; nevertheless all these things mixed together in the medical gentleman’s mind when he made his decision. Above all, it might or might not be sufficient explanation to say that Horace Hunter was a very ambitious young man, that the ring in his voice and the confidence in his manner came from a very simple resolution to rise in the world.

He liked to be seen talking so confidently to Colonel Crane on that Sunday parade. Crane was comparatively poor, but he knew People. And people who knew People knew what People were doing now; while people who didn’t know People could only wonder what in the world People would do next. A lady who came with the Duchess when she opened the local market had nodded to Crane and said, “Hello, Stork,” and the doctor had decided that it was a sort of family joke and not a small ornithological mistake. And it was the Duchess who had started all that racing on stilts, which the Vernon-Smiths had introduced at their house. But it would have been devilish awkward not to know what Mrs. Vernon-Smith meant when she said, “Of course you stilt.” You never knew what they would start next. It was strange to imagine that he would ever begin to see vegetable hats here and there, but you never could tell. His first medical impulse was to add a straitjacket to the Colonel’s unusual costume. But Crane did not look like a madman, and certainly did not look like a man who was joking. He took it quite naturally. And one thing was certain:if it really was the latest fashion thing, the doctor must take it as naturally as the Colonel did. So he said it was a fine day, and was very happy to learn that there was no disagreement on that question.

The doctor’s dilemma, if we may use the phrase, was the whole neighbourhood’s dilemma. The doctor’s decision was also the whole neighbourhood’s decision. It was not so much that most of the good people there shared Hunter’s serious social ambitions, but rather that negative and cautious decisions were natural for them. They did not want other people to bother them about how they lived; and they followed the same principle by not bothering others. They also felt that the polite and respectable military gentleman would not be a very easy person to bother. The result was that the Colonel carried his monstrous green hat about the streets of that suburb for nearly a week, and nobody ever mentioned the subject to him. It was about the end of that time (while the doctor had been scanning the horizon for aristocrats crowned with cabbage, and, not seeing any, was collecting his courage to speak) that the final interruption came, and with the interruption the explanation.

The Colonel looked like he had completely forgotten all about the hat. He took it off and put it on like any other hat; he hung it on the hat-peg in his narrow front hall where there was nothing else but his sword and an old brown map of the seventeenth century. He gave it to Archer when that loyal man insisted on his official right to hold it. Archer did not insist on his official right to brush it, because he was afraid it could fall to pieces; but he occasionally gave it a cautious shake, accompanied by a look of restrained dislike. But the Colonel himself never showed any signs of either liking or disliking it. The unconventional thing had already become one of his conventions – the conventions which he never thought about enough to break. So it is probable that what at last happened was as much of a surprise to him as to anybody. Anyway, the explanation, or explosion, came in the following way.

Mr. Vernon-Smith was a small, neat gentleman with a big nose, dark moustache, and dark eyes with a constant expression of anxiety, though nobody knew what he was so anxious about in his very solid social life. He was a friend of Dr. Hunter; you could almost say a humble friend. He had the negative snobbishness that could only admire the positive and progressive snobbishness of that social figure. A man like Dr. Hunter likes to have a man like Mr. Smith, because he can pose as a perfect man of the world before him. What is more extraordinary is that a man like Mr. Smith really likes to have a man like Dr. Hunter to pose and to show his superiority. Anyhow, at one moment Vernon-Smith decided to hint that the new hat of his neighbour Crane did not look like it was from a fashion magazine. And Dr. Hunter, bursting with his secrets, called this idea stupid and made jokes about it. With calculated, confident gestures, with large phrases full of allusions, he left on his friend’s mind the impression that the whole social world would be destroyed, if anyone said a word on such a delicate topic. Mr. Vernon-Smith formed a general idea that the Colonel would explode with a loud bang at the slightest hint on vegetables, or any word which sounded just a little bit like ‘hat’. As usually happens in such cases, the words he was forbidden to say repeated themselves constantly in his mind with the rhythm of his pulse. At the moment he wanted to call all houses hats and all visitors vegetables.

When Crane came out of his front gate that morning he found his neighbour Vernon-Smith standing outside, between a tree and a lamp-post, talking to a young lady, a distant cousin of his family. This girl was an art student – a little too independent for the standards of this neighbourhood. Her brown hair was cut very short, and the Colonel did not admire short haircuts. On the other hand, she had a rather attractive face, with honest brown eyes a little too wide apart, which diminished the impression of beauty but increased the impression of honesty. She also had a very fresh and natural voice, and the Colonel had often heard it calling out scores at tennis on the other side of the garden wall. In some way it made him feel old; at least, he was not sure whether he felt older than he was, or younger than he was supposed to be. It was not until they met under the lamp-post that he knew her name was Audrey Smith; and he was thankful for the simple short name. Mr. Vernon-Smith presented her, and very nearly said:“May I introduce my cabbage?” instead of “my cousin.”

The Colonel, without a change in his intonation, said it was a fine day. And his neighbour, happy to escape from a very difficult situation, continued the conversation cheerfully. His manner, like when he came to local meetings and committees, was at once hesitating and confident.

“This young lady is going into Art,” he said; “a poor prospect, isn’t it? I expect we will see her drawing in chalk on the pavement and expecting us to throw a penny into the – into a tray, or something.” Here he escaped from another danger. “But of course, she thinks she’s going to be a Royal Academician[5].”

“I hope not,” said the young woman hotly. “Pavement artists are much more honest than most of the Royal Academicians.”

“I wish those friends of yours didn’t give you such revolutionary ideas,” said Mr. Vernon-Smith. “My cousin knows the most dreadful eccentrics, vegetarians and – mad Socialists.” He decided to say it, feeling that vegetarians were not quite the same as vegetables; and he felt sure the Colonel would share his horror of Socialists.

“People who want to be equal, and all that. What I say is – we’re not equal and we never can be. As I always say to Audrey – if all the property were divided tomorrow, it would go back into the same hands the next day. It’s a law of nature, and if a man thinks he can get round a law of nature, why, he’s talking through his – I mean, he’s as mad as a – “

Trying to escape from the image in his head, he was searching madly in his mind for the alternative of a March hare[6]. But before he could find it, the girl had cut in and completed his sentence. She smiled calmly, and said in her clear and ringing tones:

“As mad as Colonel Crane’s hatter.”

It is not unjust to Mr. Vernon-Smith to say that he ran as from a dynamite explosion. It would be unjust to say that he left a lady in distress, because she did not look in the least like a distressed lady, and he himself was a very distressed gentleman. He tried to ask her to go indoors, and then vanished there himself with a random apology. But the other two took no notice of him; they continued to confront each other, and both were smiling.

“I think you must be the bravest man in England,” she said. “I don’t mean anything about the war, or your medal and all that; I mean about this. Oh, yes, I know a little about this, but there’s one thing I don’t know. Why do you do it?”

“I think it is you who are the bravest woman in England,” he answered, “or, at any rate, the bravest person in these parts. I’ve walked about this town for a week, feeling like the last fool on Earth, and expecting somebody to say something. And not a soul has said a word. They all seem to be afraid of saying the wrong thing.”

“I think they’re deadly,” said Miss Smith. “And if they don’t have cabbages for hats, it’s only because they have turnips for heads.”

“No,” said the Colonel gently, “I have many generous and friendly neighbours here, including your cousin. Believe me, there is a reason why people have conventions, and the world is wiser than you know. You are too young not to be intolerant. But I can see you’ve got the fighting spirit; that is the best part of youth and intolerance.”

“You see, I can’t keep calm when they say all these polished vulgarities about everything – look at what he said about Socialism.” answered the girl.

“It was a little superficial,” said Crane with a smile.

“And that,” she concluded, “is why I admire your hat, though I don’t know why you wear it.”

This trivial conversation had a curious effect on the Colonel. There went with it a sort of warmth and a sense of crisis that he had not known since the war. A sudden purpose formed itself in his mind, and he spoke like one stepping across a border.