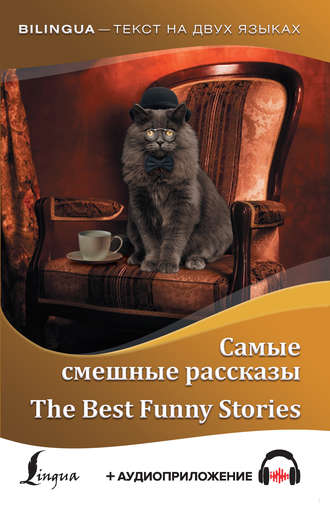

Джером К. Джером

Самые смешные рассказы / The Best Funny Stories (+ аудиоприложение)

Упражнения

1. Smoking and drinking

a) Ответьте на вопросы:

1. Where were the three people sitting?

______________________________

2. Why did the narrator’s friend prefer Belgian cigars?

______________________________

3. How did the cheap wine help the narrator’s friend?

______________________________

4. How much does the wine cost?

______________________________

b) Найдите в тексте антонимы к словам:

c) Расскажите о своих привычках. Постарайтесь ответить на следующие вопросы:

1. Do you have any habits?

______________________________

2. Are they good or bad?

______________________________

3. If they are bad, have you tried to kick them?

______________________________

4. If they are good, was it difficult for you to get them?

______________________________

2. Falling asleep

a) Ответьте на вопросы:

1. Was the man happy when his wife died?

______________________________

2. What was the man’s favourite place to sit?

______________________________

3. Why was the new wife a poor substitute for him?

______________________________

4. Was it easy for a man to fall asleep? Why?

______________________________

b) Образуйте от этих слов антонимы с помощью приставки un-:

c) Поставьте слова в скобках в Past Simple:

1. His face _____________ (to brighten) at the sound of her words.

2. The doctor _____________ (to want) to give him tons of sleeping pills.

3. Her voice _____________ (to be) very exhausted.

4. I _____________ (to decide) to bet half a sovereign.

3. The editor’s story

a) Соедините слова с их определениями:

b) Напишите небольшой текст о своем распорядке дня.

At what time do you get up, eat your breakfast…

__________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________

4. The end of the editor’s story

a) Ответьте на вопросы:

1. How did the man find out the source of his problem?

__________________________________________________________

2. What was the only solution for the poor man?

__________________________________________________________

3. At what time did the man have dinner?

__________________________________________________________

4. Did the editor get his half-sovereign?

__________________________________________________________

b) Найдите в тексте антонимы к этим словам:

Should We Say What We Think, or Think What We Say?

Jerome K. Jerome

A mad friend of mine says that the main word of the age is Make-Believe. He claims that all social intercourse is founded on make-believe. A servant enters to say that Mr. and Mrs. Bore are in the living-room.

“Oh, damn!” says the man.

“Hush!” says the woman. “Shut the door, Susan. How often am I to tell you never to leave the door open?”

The man creeps upstairs on tiptoe and enters his study room. The woman tries not to show her feelings, and then enters the living-room with a smile. She looks as if an angel has arrived. She says how delighted she is to see the Bores—how good it was of them to come. Why did they not bring more Bores with them? Where is naughty Bore junior? Why does he never come to see her now? She will have to be really angry with him. And sweet little Flossie Bore? Too young to visit friends! Nonsense.

The Bores, who had hoped that she was not at home—who have only come because the etiquette book told them that they had to come at least four times in the season, explain how they have been trying and trying to come.

“This afternoon,” says Mrs. Bore, “we decided to come for sure. ‘John, dear,’ I said this morning, ‘I shall go and see dear Mrs. Bounder this afternoon, no matter what happens.’”

It looks like the Prince of Wales, who wanted to visit the Bores, was told that he could not come in. He might call again in the evening or come some other day.

That afternoon the Bores were going to enjoy themselves in their own way; they were going to see Mrs. Bounder.

“And how is Mr. Bounder?” asks Mrs. Bore.

Mrs. Bounder remains mute for a moment. She can hear how he goes downstairs. She hears how the front door softly opens and closes.

And thus it is, not only with the Bores and Bounders, but even with us who are not Bores or Bounders. Any society is founded on the make-believe that everybody is charming; that we are delighted to see everybody; that everybody is delighted to see us; that it is so good of everybody to come; that we are desolate at the thought that they really must go now.

What will we prefer—to stop and finish our cigar or to hasten into the living-room to hear Miss Screecher’s songs? Miss Screecher does not want to sing; but if we insist—We do insist. Miss Screecher consents. We are trying not to look at one another. We sit and examine the ceiling. Miss Screecher finishes, and rises.

“But it was so short,” we say. Is Miss Screecher sure that was the end? Didn’t she miss a verse? Miss Screecher assures us that the fault is the composer’s. But she knows another. So our faces lighten again with gladness.

Our host’s wine is always the best we have ever tasted. No, not another glass; we dare not—doctor’s orders, very strict. Our host’s cigar! We did not know they made such cigars in this world. No, we really cannot smoke another. Well, if he insists, may we put it in our pocket? The truth is, we do not like to smoke.

Our hostess’s coffee! Will she tell us her secret?

The baby! The usual baby—we have seen it. To be honest, we do not like babies a lot. But this baby! It is just the kind we wanted for ourselves.

Little Janet’s recitation: “A Visit to the Dentist”! This is genius, surely. She must train for the stage. Her mother does not like the stage. But the theatre will lose such talent.

Every bride is beautiful. Every bride looks charming in a simple dress of—for further particulars see local papers. Every marriage is a cause for universal rejoicing. With our wine-glass in our hand we picture the best life for them. How can it be otherwise? She, the daughter of her mother. (Cheers.) He—well, we all know him. (More cheers.)

We carry our make-believe even into our religion. We sit in church, and say to the God, that we are miserable worms—that there is no good in us. It does us no harm, we must do it anyway.

We make-believe that every woman is good, that every man is honest—until they show us, against our will, that they are not. Then we become very angry with them, and explain to them that they are such sinners, and are not to mix with us perfect people.

Everybody goes to a better world when they have got all they can here. We stand around the open grave and tell each other so. The clergyman is so assured of it that, to save time, they have written out the formula for him and had it printed in a little book.

When I was a child, I was very surprised that everybody went to heaven. I was thinking about all the people that had died, there were too many people there. Almost I felt sorry for the Devil, forgotten and abandoned. I saw him in imagination, a lonely old gentleman, sitting at his gate day after day, doing nothing. An old nurse whom I told my ideas was sure that he would get me anyhow. Maybe I was an evil-hearted boy. But the thought of how he will welcome me, the only human being that he had seen for years, made me almost happy.

At every public meeting the chief speaker is always “a good fellow.” The man from Mars, reading our newspapers, will be convinced that every Member of Parliament was a jovial, kindly, high-hearted, generous-souled saint. We have always listened with pleasure to the brilliant speech of our friend who has just sat down.

The higher one ascends in the social scale, the wider becomes the make-believe. When anything sad happens to a very important person, the lesser people round about him hardly can live. So one wonders sometimes how it is the world continues to exist.

Once upon a time a certain good and great man became ill. I read in the newspaper that the whole nation was in grief. People dining in restaurants dropped their heads upon the table and sobbed. Strangers, meeting in the street, cried like little children. I was abroad at the time, but began to return home. I almost felt ashamed to go. I looked at myself in the mirror, and was shocked at my own appearance: there was a man who had not been in trouble for weeks. Surely, I had a shallow nature. I had had luck with a play in America, and I just could not look grief-stricken. There were moments when I found myself whistling!

The first man I talked to on Dover pier was a Customs House official. He appeared quite pleased when he found 48 cigars. He demanded the tax, and chuckled when he got it.

On Dover platform a little girl laughed because a lady dropped a handbox on a dog; but then children are always callous—or, perhaps, she had not heard the news.

What astonished me most, however, was to find in the train a respectable looking man who was reading a comic journal. True, he did not laugh much; but what was a grief-stricken citizen doing with a comic journal, anyhow? I had come to the conclusion that we English must be a people of wonderful self-control. The day before, as newspapers wrote, the whole country was in serious danger of a broken heart. “We have cried all day,” they had said to themselves, “we have cried all night. Now let us live once again.” Some of them—I noticed it in the hotel dining-room that evening—were returning to their food again.

We make believe about quite serious things. In war, each country’s soldiers are always the most courageous in the world. The other country’s soldiers are always treacherous and sly; that is why they sometimes win. Literature is the art of make-believe.

“Now all of you sit round and throw your pennies in the cap,” says the author, “and I will pretend that there lives in Bayswater a young lady named Angelina, who is the most beautiful young lady that ever existed. And in Notting Hill, we will pretend, there lives a young man named Edwin, who is in love with Angelina.”

And then, if there are some pennies in the cap, the author pretends that Angelina thought this and said that, and that Edwin did all sorts of wonderful things. We know he is making it all up. We know he is making up just to please us. But we know well enough that if we stop to throw the pennies into the cap, the author can do another things.

The manager bangs his drum.

“Come here! come here!” he cries, “we are going to pretend that Mrs. Johnson is a princess, and old man Johnson is going to pretend to be a pirate. Come here, come here, and be in time!”

So Mrs. Johnson, pretending to be a princess, comes out of a paper house that we agree to pretend is a castle; and old man Johnson, pretending to be a pirate, is swimming in the thing we agree to pretend is the ocean. Mrs. Johnson pretends to be in love with him, but we know she is not. And Johnson pretends to be a very terrible person; and Mrs. Johnson pretends, till eleven o’clock, to believe it. And we pay money to sit for two hours and listen to them.

But as I explained at the beginning, my friend is a mad person.