Редьярд Джозеф Киплинг

Plain Tales from the Hills

CUPID’S ARROWS

Pit where the buffalo cooled his hide,

By the hot sun emptied, and blistered and dried;

Log in the reh-grass, hidden and alone;

Bund where the earth-rat’s mounds are strown:

Cave in the bank where the sly stream steals;

Aloe that stabs at the belly and heels,

Jump if you dare on a steed untried —

Safer it is to go wide – go wide!

Hark, from in front where the best men ride: —

“Pull to the off, boys! Wide! Go wide!”

The Peora Hunt.

Once upon a time there lived at Simla a very pretty girl, the daughter of a poor but honest District and Sessions Judge. She was a good girl, but could not help knowing her power and using it. Her Mamma was very anxious about her daughter’s future, as all good Mammas should be.

When a man is a Commissioner and a bachelor and has the right of wearing open-work jam-tart jewels in gold and enamel on his clothes, and of going through a door before every one except a Member of Council, a Lieutenant-Governor, or a Viceroy, he is worth marrying. At least, that is what ladies say. There was a Commissioner in Simla, in those days, who was, and wore, and did, all I have said. He was a plain man – an ugly man – the ugliest man in Asia, with two exceptions. His was a face to dream about and try to carve on a pipe-head afterwards. His name was Saggott – Barr-Saggott – Anthony Barr-Saggott and six letters to follow. Departmentally, he was one of the best men the Government of India owned. Socially, he was like a blandishing gorilla.

When he turned his attentions to Miss Beighton, I believe that Mrs. Beighton wept with delight at the reward Providence had sent her in her old age.

Mr. Beighton held his tongue. He was an easy-going man.

Now a Commissioner is very rich. His pay is beyond the dreams of avarice – is so enormous that he can afford to save and scrape in a way that would almost discredit a Member of Council. Most Commissioners are mean; but Barr-Saggott was an exception. He entertained royally; he horsed himself well; he gave dances; he was a power in the land; and he behaved as such.

Consider that everything I am writing of took place in an almost pre-historic era in the history of British India. Some folk may remember the years before lawn-tennis was born when we all played croquet. There were seasons before that, if you will believe me, when even croquet had not been invented, and archery – which was revived in England in 1844 – was as great a pest as lawn-tennis is now. People talked learnedly about “holding” and “loosing,” “steles,” “reflexed bows,” “56-pound bows,” “backed” or “self-yew bows,” as we talk about “rallies,” “volleys,” “smashes,” “returns,” and “16-ounce rackets.”

Miss Beighton shot divinely over ladies’ distance – 60 yards, that is – and was acknowledged the best lady archer in Simla. Men called her “Diana of Tara-Devi.”

Barr-Saggott paid her great attention; and, as I have said, the heart of her mother was uplifted in consequence. Kitty Beighton took matters more calmly. It was pleasant to be singled out by a Commissioner with letters after his name, and to fill the hearts of other girls with bad feelings. But there was no denying the fact that Barr-Saggott was phenomenally ugly; and all his attempts to adorn himself only made him more grotesque. He was not christened “The Langur” – which means gray ape – for nothing. It was pleasant, Kitty thought, to have him at her feet, but it was better to escape from him and ride with the graceless Cubbon – the man in a Dragoon Regiment at Umballa – the boy with a handsome face, and no prospects. Kitty liked Cubbon more than a little. He never pretended for a moment the he was anything less than head over heels in love with her; for he was an honest boy. So Kitty fled, now and again, from the stately wooings of Barr-Saggott to the company of young Cubbon, and was scolded by her Mamma in consequence. “But, Mother,” she said, “Mr. Saggot is such – such a – is so FEARFULLY ugly, you know!”

“My dear,” said Mrs. Beighton, piously, “we cannot be other than an all-ruling Providence has made us. Besides, you will take precedence of your own Mother, you know! Think of that and be reasonable.”

Then Kitty put up her little chin and said irreverent things about precedence, and Commissioners, and matrimony. Mr. Beighton rubbed the top of his head; for he was an easy-going man.

Late in the season, when he judged that the time was ripe, Barr-Saggott developed a plan which did great credit to his administrative powers. He arranged an archery tournament for ladies, with a most sumptuous diamond-studded bracelet as prize. He drew up his terms skilfully, and every one saw that the bracelet was a gift to Miss Beighton; the acceptance carrying with it the hand and the heart of Commissioner Barr-Saggott. The terms were a St. Leonard’s Round – thirty-six shots at sixty yards – under the rules of the Simla Toxophilite Society.

All Simla was invited. There were beautifully arranged tea-tables under the deodars at Annandale, where the Grand Stand is now; and, alone in its glory, winking in the sun, sat the diamond bracelet in a blue velvet case. Miss Beighton was anxious – almost too anxious to compete. On the appointed afternoon, all Simla rode down to Annandale to witness the Judgment of Paris turned upside down. Kitty rode with young Cubbon, and it was easy to see that the boy was troubled in his mind. He must be held innocent of everything that followed. Kitty was pale and nervous, and looked long at the bracelet. Barr-Saggott was gorgeously dressed, even more nervous than Kitty, and more hideous than ever.

Mrs. Beighton smiled condescendingly, as befitted the mother of a potential Commissioneress, and the shooting began; all the world standing in a semicircle as the ladies came out one after the other.

Nothing is so tedious as an archery competition. They shot, and they shot, and they kept on shooting, till the sun left the valley, and little breezes got up in the deodars, and people waited for Miss Beighton to shoot and win. Cubbon was at one horn of the semicircle round the shooters, and Barr-Saggott at the other. Miss Beighton was last on the list. The scoring had been weak, and the bracelet, PLUS Commissioner Barr-Saggott, was hers to a certainty.

The Commissioner strung her bow with his own sacred hands. She stepped forward, looked at the bracelet, and her first arrow went true to a hair – full into the heart of the “gold” – counting nine points.

Young Cubbon on the left turned white, and his Devil prompted Barr-Saggott to smile. Now horses used to shy when Barr-Saggott smiled. Kitty saw that smile. She looked to her left-front, gave an almost imperceptible nod to Cubbon, and went on shooting.

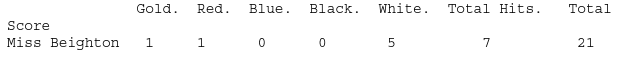

I wish I could describe the scene that followed. It was out of the ordinary and most improper. Miss Kitty fitted her arrows with immense deliberation, so that every one might see what she was doing. She was a perfect shot; and her 46-pound bow suited her to a nicety. She pinned the wooden legs of the target with great care four successive times. She pinned the wooden top of the target once, and all the ladies looked at each other. Then she began some fancy shooting at the white, which, if you hit it, counts exactly one point. She put five arrows into the white. It was wonderful archery; but, seeing that her business was to make “golds” and win the bracelet, Barr-Saggott turned a delicate green like young water-grass. Next, she shot over the target twice, then wide to the left twice – always with the same deliberation – while a chilly hush fell over the company, and Mrs. Beighton took out her handkerchief. Then Kitty shot at the ground in front of the target, and split several arrows. Then she made a red – or seven points – just to show what she could do if she liked, and finished up her amazing performance with some more fancy shooting at the target-supports. Here is her score as it was picked off: —

Barr-Saggott looked as if the last few arrowheads had been driven into his legs instead of the target’s, and the deep stillness was broken by a little snubby, mottled, half-grown girl saying in a shrill voice of triumph: “Then I’VE won!”

Mrs. Beighton did her best to bear up; but she wept in the presence of the people. No training could help her through such a disappointment. Kitty unstrung her bow with a vicious jerk, and went back to her place, while Barr-Saggott was trying to pretend that he enjoyed snapping the bracelet on the snubby girl’s raw, red wrist. It was an awkward scene – most awkward. Every one tried to depart in a body and leave Kitty to the mercy of her Mamma.

But Cubbon took her away instead, and – the rest isn’t worth printing.

HIS CHANCE IN LIFE

Then a pile of heads be laid —

Thirty thousand heaped on high —

All to please the Kafir maid,

Where the Oxus ripples by.

Grimly spake Atulla Khan: —

“Love hath made this thing a Man.”

Oatta’s Story.

If you go straight away from Levees and Government House Lists, past Trades’ Balls – far beyond everything and everybody you ever knew in your respectable life – you cross, in time, the Border line where the last drop of White blood ends and the full tide of Black sets in. It would be easier to talk to a new made Duchess on the spur of the moment than to the Borderline folk without violating some of their conventions or hurting their feelings. The Black and the White mix very quaintly in their ways. Sometimes the White shows in spurts of fierce, childish pride – which is Pride of Race run crooked – and sometimes the Black in still fiercer abasement and humility, half heathenish customs and strange, unaccountable impulses to crime. One of these days, this people – understand they are far lower than the class whence Derozio, the man who imitated Byron, sprung – will turn out a writer or a poet; and then we shall know how they live and what they feel. In the meantime, any stories about them cannot be absolutely correct in fact or inference.

Miss Vezzis came from across the Borderline to look after some children who belonged to a lady until a regularly ordained nurse could come out. The lady said Miss Vezzis was a bad, dirty nurse and inattentive. It never struck her that Miss Vezzis had her own life to lead and her own affairs to worry over, and that these affairs were the most important things in the world to Miss Vezzis. Very few mistresses admit this sort of reasoning. Miss Vezzis was as black as a boot, and to our standard of taste, hideously ugly. She wore cotton-print gowns and bulged shoes; and when she lost her temper with the children, she abused them in the language of the Borderline – which is part English, part Portuguese, and part Native. She was not attractive; but she had her pride, and she preferred being called “Miss Vezzis.”

Every Sunday she dressed herself wonderfully and went to see her Mamma, who lived, for the most part, on an old cane chair in a greasy tussur-silk dressing-gown and a big rabbit-warren of a house full of Vezzises, Pereiras, Ribieras, Lisboas and Gansalveses, and a floating population of loafers; besides fragments of the day’s bazar, garlic, stale incense, clothes thrown on the floor, petticoats hung on strings for screens, old bottles, pewter crucifixes, dried immortelles, pariah puppies, plaster images of the Virgin, and hats without crowns. Miss Vezzis drew twenty rupees a month for acting as nurse, and she squabbled weekly with her Mamma as to the percentage to be given towards housekeeping. When the quarrel was over, Michele D’Cruze used to shamble across the low mud wall of the compound and make love to Miss Vezzis after the fashion of the Borderline, which is hedged about with much ceremony. Michele was a poor, sickly weed and very black; but he had his pride. He would not be seen smoking a huqa for anything; and he looked down on natives as only a man with seven-eighths native blood in his veins can. The Vezzis Family had their pride too. They traced their descent from a mythical plate-layer who had worked on the Sone Bridge when railways were new in India, and they valued their English origin. Michele was a Telegraph Signaller on Rs. 35 a month. The fact that he was in Government employ made Mrs. Vezzis lenient to the shortcomings of his ancestors.

There was a compromising legend – Dom Anna the tailor brought it from Poonani – that a black Jew of Cochin had once married into the D’Cruze family; while it was an open secret that an uncle of Mrs. D’Cruze was at that very time doing menial work, connected with cooking, for a Club in Southern India! He sent Mrs D’Cruze seven rupees eight annas a month; but she felt the disgrace to the family very keenly all the same.

However, in the course of a few Sundays, Mrs. Vezzis brought herself to overlook these blemishes and gave her consent to the marriage of her daughter with Michele, on condition that Michele should have at least fifty rupees a month to start married life upon. This wonderful prudence must have been a lingering touch of the mythical plate-layer’s Yorkshire blood; for across the Borderline people take a pride in marrying when they please – not when they can.

Having regard to his departmental prospects, Miss Vezzis might as well have asked Michele to go away and come back with the Moon in his pocket. But Michele was deeply in love with Miss Vezzis, and that helped him to endure. He accompanied Miss Vezzis to Mass one Sunday, and after Mass, walking home through the hot stale dust with her hand in his, he swore by several Saints, whose names would not interest you, never to forget Miss Vezzis; and she swore by her Honor and the Saints – the oath runs rather curiously; “In nomine Sanctissimae – ” (whatever the name of the she-Saint is) and so forth, ending with a kiss on the forehead, a kiss on the left cheek, and a kiss on the mouth – never to forget Michele.

Next week Michele was transferred, and Miss Vezzis dropped tears upon the window-sash of the “Intermediate” compartment as he left the Station.

If you look at the telegraph-map of India you will see a long line skirting the coast from Backergunge to Madras. Michele was ordered to Tibasu, a little Sub-office one-third down this line, to send messages on from Berhampur to Chicacola, and to think of Miss Vezzis and his chances of getting fifty rupees a month out of office hours. He had the noise of the Bay of Bengal and a Bengali Babu for company; nothing more. He sent foolish letters, with crosses tucked inside the flaps of the envelopes, to Miss Vezzis.

When he had been at Tibasu for nearly three weeks his chance came.

Never forget that unless the outward and visible signs of Our Authority are always before a native he is as incapable as a child of understanding what authority means, or where is the danger of disobeying it. Tibasu was a forgotten little place with a few Orissa Mohamedans in it. These, hearing nothing of the Collector-Sahib for some time, and heartily despising the Hindu Sub-Judge, arranged to start a little Mohurrum riot of their own. But the Hindus turned out and broke their heads; when, finding lawlessness pleasant, Hindus and Mahomedans together raised an aimless sort of Donnybrook just to see how far they could go. They looted each other’s shops, and paid off private grudges in the regular way. It was a nasty little riot, but not worth putting in the newspapers.

Michele was working in his office when he heard the sound that a man never forgets all his life – the “ah-yah” of an angry crowd. [When that sound drops about three tones, and changes to a thick, droning ut, the man who hears it had better go away if he is alone.] The Native Police Inspector ran in and told Michele that the town was in an uproar and coming to wreck the Telegraph Office. The Babu put on his cap and quietly dropped out of the window; while the Police Inspector, afraid, but obeying the old race-instinct which recognizes a drop of White blood as far as it can be diluted, said: – “What orders does the Sahib give?”

The “Sahib” decided Michele. Though horribly frightened, he felt that, for the hour, he, the man with the Cochin Jew and the menial uncle in his pedigree, was the only representative of English authority in the place. Then he thought of Miss Vezzis and the fifty rupees, and took the situation on himself. There were seven native policemen in Tibasu, and four crazy smooth-bore muskets among them. All the men were gray with fear, but not beyond leading. Michele dropped the key of the telegraph instrument, and went out, at the head of his army, to meet the mob. As the shouting crew came round a corner of the road, he dropped and fired; the men behind him loosing instinctively at the same time.

The whole crowd – curs to the backbone – yelled and ran; leaving one man dead, and another dying in the road. Michele was sweating with fear, but he kept his weakness under, and went down into the town, past the house where the Sub-Judge had barricaded himself. The streets were empty. Tibasu was more frightened than Michele, for the mob had been taken at the right time.

Michele returned to the Telegraph-Office, and sent a message to Chicacola asking for help. Before an answer came, he received a deputation of the elders of Tibasu, telling him that the Sub-Judge said his actions generally were “unconstitutional,” and trying to bully him. But the heart of Michele D’Cruze was big and white in his breast, because of his love for Miss Vezzis, the nurse-girl, and because he had tasted for the first time Responsibility and Success. Those two make an intoxicating drink, and have ruined more men than ever has Whiskey. Michele answered that the Sub-Judge might say what he pleased, but, until the Assistant Collector came, the Telegraph Signaller was the Government of India in Tibasu, and the elders of the town would be held accountable for further rioting. Then they bowed their heads and said: “Show mercy!” or words to that effect, and went back in great fear; each accusing the other of having begun the rioting.

Early in the dawn, after a night’s patrol with his seven policemen, Michele went down the road, musket in hand, to meet the Assistant Collector, who had ridden in to quell Tibasu. But, in the presence of this young Englishman, Michele felt himself slipping back more and more into the native, and the tale of the Tibasu Riots ended, with the strain on the teller, in an hysterical outburst of tears, bred by sorrow that he had killed a man, shame that he could not feel as uplifted as he had felt through the night, and childish anger that his tongue could not do justice to his great deeds. It was the White drop in Michele’s veins dying out, though he did not know it.

But the Englishman understood; and, after he had schooled those men of Tibasu, and had conferred with the Sub-Judge till that excellent official turned green, he found time to draught an official letter describing the conduct of Michele. Which letter filtered through the Proper Channels, and ended in the transfer of Michele up-country once more, on the Imperial salary of sixty-six rupees a month.

So he and Miss Vezzis were married with great state and ancientry; and now there are several little D’Cruzes sprawling about the verandahs of the Central Telegraph Office.

But, if the whole revenue of the Department he serves were to be his reward Michele could never, never repeat what he did at Tibasu for the sake of Miss Vezzis the nurse-girl.

Which proves that, when a man does good work out of all proportion to his pay, in seven cases out of nine there is a woman at the back of the virtue.

The two exceptions must have suffered from sunstroke.

WATCHES OF THE NIGHT

What is in the Brahmin’s books that is in the Brahmin’s heart.

Neither you nor I knew there was so much evil in the world.

Hindu Proverb.

This began in a practical joke; but it has gone far enough now, and is getting serious.

Platte, the Subaltern, being poor, had a Waterbury watch and a plain leather guard.

The Colonel had a Waterbury watch also, and for guard, the lip-strap of a curb-chain. Lip-straps make the best watch guards. They are strong and short. Between a lip-strap and an ordinary leather guard there is no great difference; between one Waterbury watch and another there is none at all. Every one in the station knew the Colonel’s lip-strap. He was not a horsey man, but he liked people to believe he had been on once; and he wove fantastic stories of the hunting-bridle to which this particular lip-strap had belonged. Otherwise he was painfully religious.

Platte and the Colonel were dressing at the Club – both late for their engagements, and both in a hurry. That was Kismet. The two watches were on a shelf below the looking-glass – guards hanging down. That was carelessness. Platte changed first, snatched a watch, looked in the glass, settled his tie, and ran. Forty seconds later, the Colonel did exactly the same thing; each man taking the other’s watch.

You may have noticed that many religious people are deeply suspicious. They seem – for purely religious purposes, of course – to know more about iniquity than the Unregenerate. Perhaps they were specially bad before they became converted! At any rate, in the imputation of things evil, and in putting the worst construction on things innocent, a certain type of good people may be trusted to surpass all others. The Colonel and his Wife were of that type. But the Colonel’s Wife was the worst. She manufactured the Station scandal, and – TALKED TO HER AYAH! Nothing more need be said. The Colonel’s Wife broke up the Laplace’s home. The Colonel’s Wife stopped the Ferris-Haughtrey engagement. The Colonel’s Wife induced young Buxton to keep his wife down in the Plains through the first year of the marriage. Whereby little Mrs. Buxton died, and the baby with her. These things will be remembered against the Colonel’s Wife so long as there is a regiment in the country.

But to come back to the Colonel and Platte. They went their several ways from the dressing-room. The Colonel dined with two Chaplains, while Platte went to a bachelor-party, and whist to follow.

Mark how things happen! If Platte’s sais had put the new saddle-pad on the mare, the butts of the territs would not have worked through the worn leather, and the old pad into the mare’s withers, when she was coming home at two o’clock in the morning. She would not have reared, bolted, fallen into a ditch, upset the cart, and sent Platte flying over an aloe-hedge on to Mrs. Larkyn’s well-kept lawn; and this tale would never have been written. But the mare did all these things, and while Platte was rolling over and over on the turf, like a shot rabbit, the watch and guard flew from his waistcoat – as an Infantry Major’s sword hops out of the scabbard when they are firing a feu de joie – and rolled and rolled in the moonlight, till it stopped under a window.

Platte stuffed his handkerchief under the pad, put the cart straight, and went home.

Mark again how Kismet works! This would not happen once in a hundred years. Towards the end of his dinner with the two Chaplains, the Colonel let out his waistcoat and leaned over the table to look at some Mission Reports. The bar of the watch-guard worked through the buttonhole, and the watch – Platte’s watch – slid quietly on to the carpet. Where the bearer found it next morning and kept it.

Then the Colonel went home to the wife of his bosom; but the driver of the carriage was drunk and lost his way. So the Colonel returned at an unseemly hour and his excuses were not accepted. If the Colonel’s Wife had been an ordinary “vessel of wrath appointed for destruction,” she would have known that when a man stays away on purpose, his excuse is always sound and original. The very baldness of the Colonel’s explanation proved its truth.

See once more the workings of Kismet! The Colonel’s watch which came with Platte hurriedly on to Mrs. Larkyn’s lawn, chose to stop just under Mrs. Larkyn’s window, where she saw it early in the morning, recognized it, and picked it up. She had heard the crash of Platte’s cart at two o’clock that morning, and his voice calling the mare names. She knew Platte and liked him. That day she showed him the watch and heard his story. He put his head on one side, winked and said: – “How disgusting! Shocking old man! with his religious training, too! I should send the watch to the Colonel’s Wife and ask for explanations.”

Mrs. Larkyn thought for a minute of the Laplaces – whom she had known when Laplace and his wife believed in each other – and answered: – “I will send it. I think it will do her good. But remember, we must NEVER tell her the truth.”

Platte guessed that his own watch was in the Colonel’s possession, and thought that the return of the lip-strapped Waterbury with a soothing note from Mrs. Larkyn, would merely create a small trouble for a few minutes. Mrs. Larkyn knew better. She knew that any poison dropped would find good holding-ground in the heart of the Colonel’s Wife.

The packet, and a note containing a few remarks on the Colonel’s calling-hours, were sent over to the Colonel’s Wife, who wept in her own room and took counsel with herself.

If there was one woman under Heaven whom the Colonel’s Wife hated with holy fervor, it was Mrs. Larkyn. Mrs. Larkyn was a frivolous lady, and called the Colonel’s Wife “old cat.” The Colonel’s Wife said that somebody in Revelations was remarkably like Mrs. Larkyn. She mentioned other Scripture people as well. From the Old Testament. [But the Colonel’s Wife was the only person who cared or dared to say anything against Mrs. Larkyn. Every one else accepted her as an amusing, honest little body.] Wherefore, to believe that her husband had been shedding watches under that “Thing’s” window at ungodly hours, coupled with the fact of his late arrival on the previous night, was…

At this point she rose up and sought her husband. He denied everything except the ownership of the watch. She besought him, for his Soul’s sake, to speak the truth. He denied afresh, with two bad words. Then a stony silence held the Colonel’s Wife, while a man could draw his breath five times.

The speech that followed is no affair of mine or yours. It was made up of wifely and womanly jealousy; knowledge of old age and sunken cheeks; deep mistrust born of the text that says even little babies’ hearts are as bad as they make them; rancorous hatred of Mrs. Larkyn, and the tenets of the creed of the Colonel’s Wife’s upbringing.

Over and above all, was the damning lip-strapped Waterbury, ticking away in the palm of her shaking, withered hand. At that hour, I think, the Colonel’s Wife realized a little of the restless suspicions she had injected into old Laplace’s mind, a little of poor Miss Haughtrey’s misery, and some of the canker that ate into Buxton’s heart as he watched his wife dying before his eyes. The Colonel stammered and tried to explain. Then he remembered that his watch had disappeared; and the mystery grew greater. The Colonel’s Wife talked and prayed by turns till she was tired, and went away to devise means for “chastening the stubborn heart of her husband.” Which translated, means, in our slang, “tail-twisting.”

You see, being deeply impressed with the doctrine of Original Sin, she could not believe in the face of appearances. She knew too much, and jumped to the wildest conclusions.

But it was good for her. It spoilt her life, as she had spoilt the life of the Laplaces. She had lost her faith in the Colonel, and – here the creed-suspicion came in – he might, she argued, have erred many times, before a merciful Providence, at the hands of so unworthy an instrument as Mrs. Larkyn, had established his guilt. He was a bad, wicked, gray-haired profligate. This may sound too sudden a revulsion for a long-wedded wife; but it is a venerable fact that, if a man or woman makes a practice of, and takes a delight in, believing and spreading evil of people indifferent to him or her, he or she will end in believing evil of folk very near and dear. You may think, also, that the mere incident of the watch was too small and trivial to raise this misunderstanding. It is another aged fact that, in life as well as racing, all the worst accidents happen at little ditches and cut-down fences. In the same way, you sometimes see a woman who would have made a Joan of Arc in another century and climate, threshing herself to pieces over all the mean worry of housekeeping. But that is another story.

Her belief only made the Colonel’s Wife more wretched, because it insisted so strongly on the villainy of men. Remembering what she had done, it was pleasant to watch her unhappiness, and the penny-farthing attempts she made to hide it from the Station. But the Station knew and laughed heartlessly; for they had heard the story of the watch, with much dramatic gesture, from Mrs. Larkyn’s lips.

Once or twice Platte said to Mrs. Larkyn, seeing that the Colonel had not cleared himself: – “This thing has gone far enough. I move we tell the Colonel’s Wife how it happened.” Mrs. Larkyn shut her lips and shook her head, and vowed that the Colonel’s Wife must bear her punishment as best she could. Now Mrs. Larkyn was a frivolous woman, in whom none would have suspected deep hate. So Platte took no action, and came to believe gradually, from the Colonel’s silence, that the Colonel must have “run off the line” somewhere that night, and, therefore, preferred to stand sentence on the lesser count of rambling into other people’s compounds out of calling hours. Platte forgot about the watch business after a while, and moved down-country with his regiment. Mrs. Larkyn went home when her husband’s tour of Indian service expired. She never forgot.

But Platte was quite right when he said that the joke had gone too far. The mistrust and the tragedy of it – which we outsiders cannot see and do not believe in – are killing the Colonel’s Wife, and are making the Colonel wretched. If either of them read this story, they can depend upon its being a fairly true account of the case, and can “kiss and make friends.”